Valar Atomics went critical

Is this part of a positive feedback loop?

On November 17th, Valar Atomics announced that its NOVA nuclear reactor core “went critical”.

The two-year-old startup created a self-sustaining chain reaction of Uranium-235, but did not enable the reaction to occur at such a rate that the core got hot and fluid was needed to cool it.

Going critical for the first time is a significant event because it is the first time the firm demonstrated the process it intends to monetize.

At the same time, it is quite possible to overstate it, and supporters of Valar Atomics in the nuclear and startup communities (who I count myself amongst) shouldn’t get carried away. In the context of the startup’s broader plans for the Ward 250 reactor architecture, the best way to describe the event is probably as an advanced development test:

only a portion of the end design was tested

nothing commercially useful was generated in the test

this was the first time a key part of the system was turned on, so to speak

Looking more broadly than this specific startup, I’m excited about the test for three key reasons.

First, it’s a massive regulatory achievement to go critical this quickly. The technological activity isn’t new (though it is new-to-Valar), but it got around government regulations in a new way.

There are two important government agencies in the US nuclear industry.

The Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) is an independent agency created to “ensure the the safe use of radioactive materials for beneficial civilian purposes while protecting people and the environment”. It does this by regulating civilian uses of nuclear materials, such as civilian power plants, through licensing and inspections.

The Department of Energy (DOE) is a cabinet-level department with the mission to “ensure America’s security and prosperity by addressing its energy, environmental and nuclear challenges through transformative science and technology solutions”. Among other things, it supports R&D relating to nuclear energy and manages government-owned nuclear facilities (such as national laboratories, military nuclear reactor production, and facilities involved with the nuclear weapons lifecycle).

Over the summer, the Department of Energy started a Nuclear Reactor Pilot Program, and invited a number of companies to participate:

Valar

The goal of the program is for at least three privately funded test reactors to operate and achieve criticality under DOE authorization by July 4, 2026.

The pilot program waives the requirement for the test reactors to be licensed by the NRC. At the same time, the pilot promises to give approved designs fast-tracking for NRC licensing in the future.

While I’m concerned about overstating Valar’s achievement with this test, I cannot overstate how big a deal this is. The NRC is perhaps the slowest bureaucracy in the government, and for good reason.

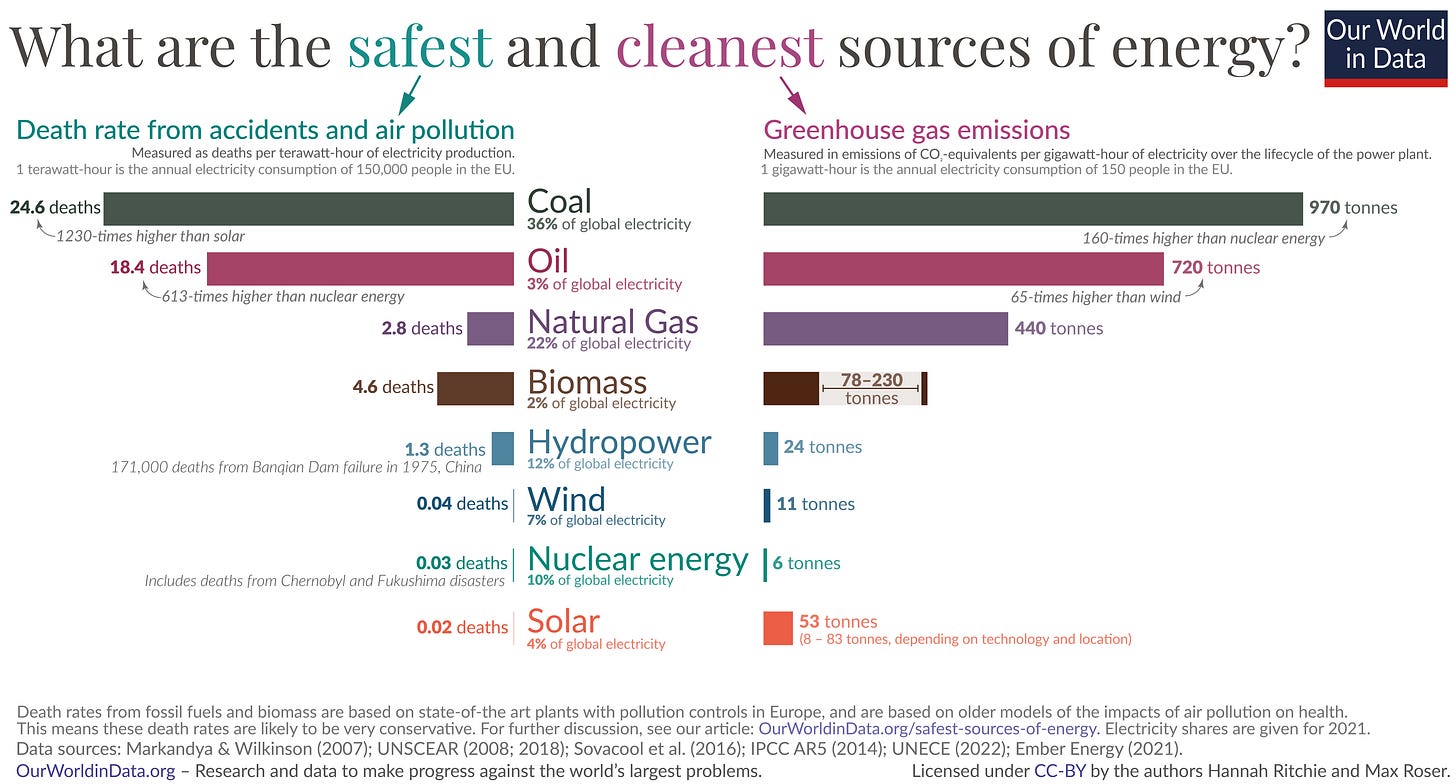

Nuclear reactors are generally very safe compared to other sources of electrical power. However, when nuclear power plants experience an anomaly, the effects are so far reaching that special scrutiny is warranted.

Having said that, it is possible to have too much of a good thing. As a deep tech advocate, and as somebody who cares about the environment, I think it takes too long to build reactors in the US today.

Valar’s achievement shows that the US DOE can move quickly on matters relating to nuclear energy when directed.

I don’t mean to suggest that this pilot program should necessarily become the norm for regulating new designs (though I’d be interested to see that discussed in more detail), or that all regulation is bad. But I think it is good to exercise, every so often, “pants-on-fire” speed in government agencies, just to show that America’s bureaucracy retains the capability.

The second reason I’m so excited about the accomplishment is that it’s a clear signal: interest in very large-scale technology projects is becoming more decentralized.

It used to be only governments, or government contractors, who would do things like design nuclear reactors or satellites or airplanes. Now, startups around the country, in different industry verticals, are taking on these projects — and demonstrating core technologies successfully!

Private investment in commercializing complex technologies isn’t a new thing, but I’ve been wondering for the past few years whether the aerospace industry would become an anomaly in our recent history in terms of the private sector’s willingness to take these risks.

Last weekend’s test demonstrates decisively that it isn’t.

I am hopeful that it will encourage more people to create startups that strive to change society on this scale.

The third reason I’m so excited about the test is that it is evidence that the private sector tradespace between business and technical complexity is changing.

I’ve often thought of great firms, judged after the fact, as having developed either a more complex business and more simple technology, or a more complex technology and more simple business.

An example of the first case is most consumer software as a service, like modern dating apps. Application-layer software that interacts with a remote server is a known, solved problem. At the same time, managing customer acquisition cost, churn, and the diversity of user journeys are thorny business layer problems that can combine to create…a deeply unpleasant user experience.

The second case might be demonstrated by transistors. These critical components in modern electronics are sold individually or assembled into integrated circuits. But the manufacturing of semiconductors that make up transistors is one of the most advanced and complex processes in the world.

Valar Atomics shows that this mental model of mine is obsolete. It’s betting big on lots of technically and regulatorily complex nuclear reactors not to produce power for the grid, but to produce Hydrogen, hydrocarbons, and power for co-located data centers and heavy industrial plants. That’s going to be a wildly complex business model, which the firm thinks is awesome and I find intriguing.

This particular type of appetite for risk seems relatively new in the post-internet world.

This is why I think it’s a great time to be investing in deep tech!

Incidentally, if you are building in deep tech and thinking about raising pre-seed/seed/Series A funding, I’d be more than happy to have a chat on professional terms!

Send me an email to find a time.

I write Molding Moonshots in a personal capacity. Nothing on Molding Moonshots should be construed as investment advice.

I hold Oklo stock. For more information, see my most recent portfolio update:

Investing in Deep Tech Q3 2025

Since we just ended Q3, it is time for an update on my publicly traded deep tech portfolio.