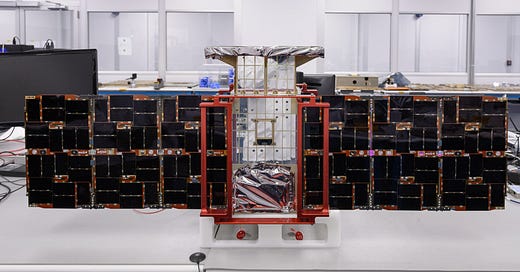

Small satellites have a special place in my heart — I started my career working on them.

In particular, I was a hardware test engineer at Terran Orbital. I worked on what’s called the “bus” — which is everything on the spacecraft except the payload. I focused in particular on hardware in the power and GN&C1 subsystems.

I came across a post on X that intrigued me last week:

space-tech has a issue with carcinization where instead of crabs everyone just keeps turning into bus providers

It’s been living “rent-free” in my head since last Thursday because while this is an anecdote, I can back that up with 3 of the biggest and most significant space startup investments this past year:

K2 Space raised a $50MM round in February — they’re building very big busses

Apex raised a $95MM Series B in June — they’re building a standardized bus at scale

Impulse Space raised a $150MM Series B at the end of September — they’re building orbital transfer vehicles2

I think it speaks on some level to one of the key issues the industry is dealing with: the satellite as a platform has become the best path to revenue.

Why is this happening?

Revenue requires a customer. That, at least, is not rocket science!

Historically, the US space industry’s biggest customer has been the DoD and US Intelligence Community. The effect of this is that the US government probably understands how to acquire and get value out of data from spacecraft better than any other potential customer out there.

It’s certainly not the only customer though.

Commercial customers exist, and more are emerging — among the most well-known are media institutions like the Wall Street Journal, which regularly purchases optical imagery from firms like Planet.

However, most of these customers are not subject matter experts about how to create value from technologies that used to be limited in their availability to people with a security clearance, and therefore accessible only to the national security establishment. I’ve mentioned this before, and I don’t think it’s a smaller problem now.

However, intra-industry networks are as strong in aerospace as other elements of tech; because of that, it’s relatively easy for startups to find various sorts of support for bus concepts since they sell into the space sector. This likely looks like launch providers, supply chains, and early (non-scalable) customers. I think this is a key driver of why so many founders building in the space sector are turning to satellite busses.

Why is it rational?

Searching for a customer within the industry is probably the easiest way for an early-stage startup to find revenue, because the sales pipeline is already in or immediately adjacent to founders’ networks.

Essentially, instead of worrying about who to sell to, startups that make busses prefer to sell to other startups that have this worry.

It’s pretty smart!

The use cases are clear, as is an understanding of what revenue looks like.

It’s also a well-understood business model. Industry incumbents like Lockheed Martin Space, Boeing, and Airbus are in the business of providing satellite busses to customers.

All these things make bus manufacturing compelling to investors as well.

Why is it a problem?

The biggest effect on this is that all the private capital tied up in satellite busses is making it more difficult for space startups that provide new, more unique, services to raise funds.

This is important to me as a venture investor because it suggests some of the big names in my industry are shying away from backing audacious ideas in the space sector. In order to back companies that will return the fund from the perspective of a pre-seed investor, I need to believe that there’s a market among investors for financial securities in those firms’ sectors.

It should be darn important to founders in the space sector, because it shows what VCs are excited to back. A great idea that requires venture capital that founders cannot sell to VCs is not going to get off the ground with VC money, and is therefore highly unlikely to pursue a VC-backed startup’s valuation trajectory. That doesn’t mean the idea is impossible or can’t be a great startup, just that the bull case financial outcome looks quite different as a consequence of the funding options available to founders.

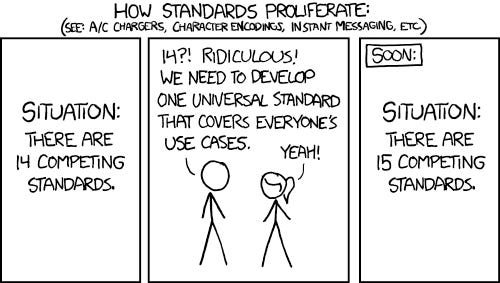

Looking at this from a broader industry perspective, what this shows me is that we’ve probably gone about as far as we can on this idea of “satellites as a hardware layer for other hardware”. The situation reminds me of the XKCD comic about standards.

Having so many different standard spacecraft of similar size doesn’t seem like it’s actually helping anybody, and probably isn’t going to lead to great outcomes for either VCs or firms building satellite busses.

I also worry that this is going to make it less likely that new approaches to launching spacecraft will be particularly useful in terms of unlocking the next steps to making humanity a multiplanetary species.

Sure, the increased mass and volume per flight will still count for something.

But if all startups are producing is standardized busses, then I’m not so sure I understand what Starship’s commercial flights will really be enabling for the rest of the industry besides bigger form factors.

We’re quite possibly past the limits of what’s going to generate a venture-scale return in the bus-as-a-business space.

The sooner everybody realizes this and figures out where to go next, the better a state the space startup ecosystem will be in.

In short, I think there needs to be more innovation in space — not just in terms of engineering, but in terms of business models as well.

What does a venture-backable satellite company look like today?

I’m not totally pessimistic on space as a venture-backable category — only on the satellite bus itself. There’s two big themes in the space sector where I see real potential to create the next out-of-this-world space company.

The first theme is that spacecraft with unique sensors and actuators in space will continue to create value on Earth. There are two elements to this.

Optical Earth Observation is saturated, but non-optical EO remains ripe for commercial exploitation because many commercial customers who would pay for the data aren’t yet properly educated about how to extract value from it. The key debate among VCs in this domain right now remains whether vertical integration between the spacecraft operator data analytics provider is a good idea or not. Two startups operating in this space are:

Wyvern Space, which operates spacecraft that capture hyperspectral data, and is also in the analytics business

Umbra Space, which explicitly promises not to enter the data analytics business

Another way to clearly create value on Earth from space is to send things from space to the ground. These might be products manufactured in space on a satellite, or things that are sent to space to await delivery to a particular time and place. Two startups operating in this space are:

Varda Space Industries, which sounds like it’s focused on pharmaceutical R&D

Inversion Space, which seems to be pursuing DoD as an anchor customer

The second theme is that new space technology, or new space applications of current technology, will open up space-centric commercial activities.

Some of these technologies are going to rely on new launch technology that’s projected to come online in the next few years, like Starship. Founders are going to literally have to bet the firm on when this technology becomes commercially available to time the market correctly.

An example of a startup actively working on this sort of thing is Astroscale, which is building a satellite to support spacecraft life extension and orbital debris removal.

It is worth keeping in mind that not all of these new technologies are going to be venture-backable; if the bull case time horizon to unicorn status is more than 10 years out, these probably should stay in the R&D lab or pursue other funding sources for now.