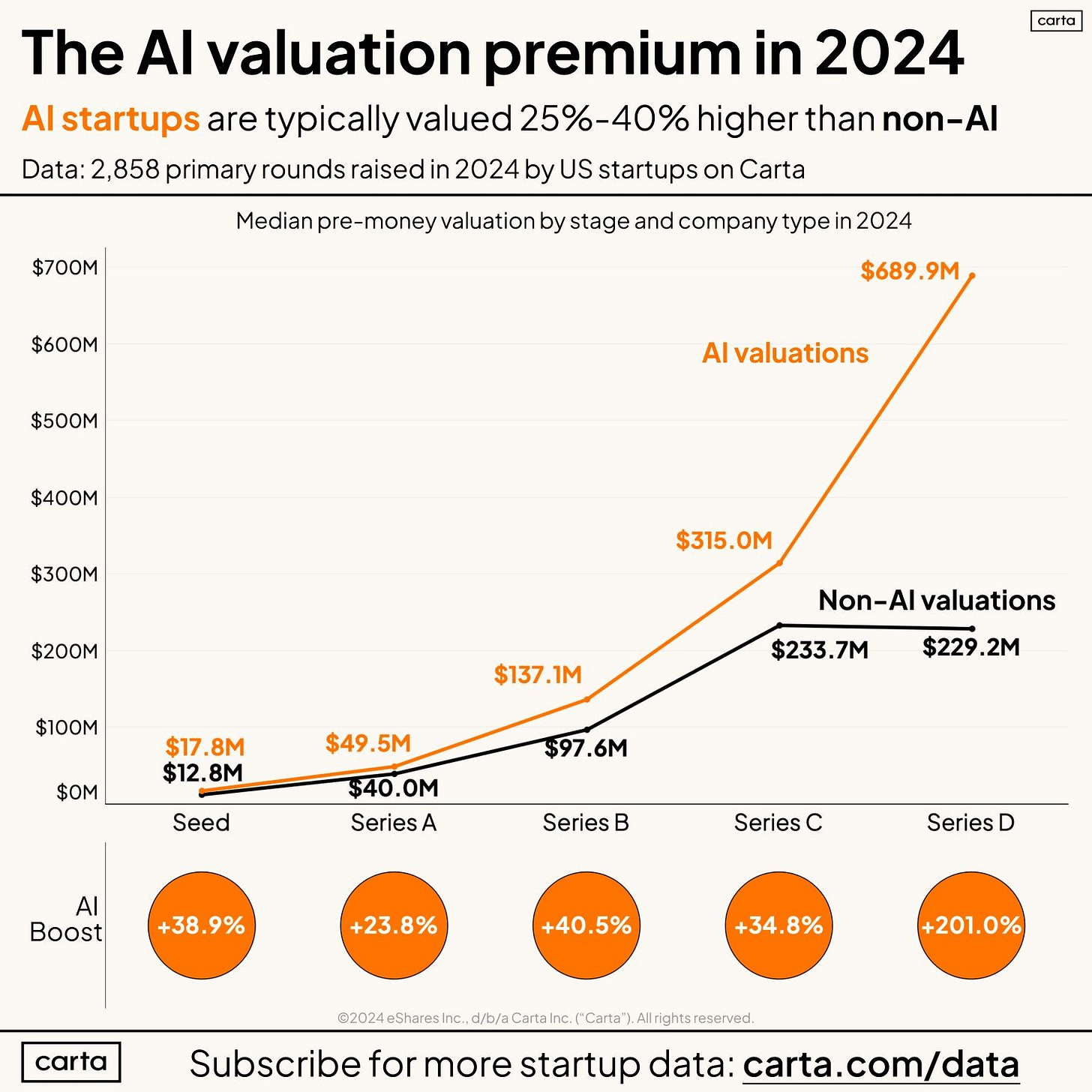

One of the things that’s impressed me recently has been the sheer size of the financing rounds being raised by AI startups. This isn’t just me though; it’s enough of a pattern that Carta has noticed it.

The premium becomes more pronounced as a startup matures. I think this is happening for two reasons.

First, I think we’re in a hype cycle. That’s driving up entry prices generally.

Second, there’s a relationship between capital employed to train AI models and the output model quality, called a “scaling law”. I suspect this law is more precisely definable as a startup matures.

To put this second point in more concrete terms, if I were looking to raise a Series B for an AI startup with a proprietary model, I’d likely have a view about how much better the next version of my model would be if I could invest $2 million into training it rather than $1 million. Investors can probably figure this out as well, though perhaps not to the same degree of precision.

Debt in AI

Once there’s a model for the relationship between invested capital and model improvement, venture debt becomes an option when fundraising.

Venture debt is the practice of funding a startup by borrowing money, which does not dilute the equity holders. Silicon Valley Bank is perhaps the most well-known provider of venture debt. SVB suggests that a key to successfully raising venture debt is doing so judiciously; a typical amount of debt to consider is 20-40% of the startup’s most recent equity round, or 6-8% of the firm’s last valuation.

In 2024, venture debt provided 15% of all startup funding in the US. Debt investments most commonly happen alongside equity investments, or as a bridge round.

Venture debt is real debt; it creates an obligation to repay the principal and interest. This typically is done in cash, though convertible debt that will be repaid in equity is sometimes negotiated.

I checked the PitchBook profiles of some of AI startups from Forbes’s AI 50 list and that I saw as industry leaders to see whether they used debt financing:

$2 billion of convertible debt from Google in Q4 2023

$4 billion of convertible debt from a syndicate including Amazon in Q1 2024

$70 million Series A including a $40 million term loan in Q4 2019

$505 million Series C including a $155 million term loan in Q2 2022

$200 million mezzanine round in Q4 20231

convertible debt round of unclear size in Q4 2023

$200 million debt round in Q1 2025

$650 million Series B including a $143 million term loan in Q3 2024

$4 billion (with additional $2 billion option) revolving line of credit in Q4 2024

$63 million Series B including a $7 million recurring revenue loan in Q1 2024

$100 million Series B including a $25 million unspecified debt instrument in Q3 2023

Some VC-backed AI startups that have raised no debt to date include:

Venture debt providers are clearly comfortable investing in AI startups. Most of these investments seem to start around Series B.

Diving in deeper, I see four archetypes:

Some firms take on no debt.

Anthropic uses convertible debt as an interim funding mechanism between larger equity rounds. This is a fairly common approach to bridge rounds when SAFEs are undesirable or unavailable.

OpenAI organized a revolving line of credit. It seems to be utilizing debt as a resource much more like a mature company than a startup.

Mistral AI, Perplexity, and Writer raised rounds that combined debt and equity.

Crusoe’s use of debt cuts across archetypes 2, 3, and 4.

Underwriting

Debt investors are more risk averse than equity investors, because debt at its core is a concrete claim on future cash from the firm, and equity is a claim on any residual value of the firm.

While VC investors who buy equity (especially before Series B) understand that companies failing is unfortunate but also normative for firms at that stage, debt investing works on a different model. Debt investing works well only when the investor is confident they’re not going to lose the principal. That drives venture debt funds’ approaches to underwriting investments.

Having said that, their underwriting processes differ significantly from venture capitalists. I’ve heard anecdotally that some of the key elements lenders look at when deciding whether or not to offer a loan to a startup (and if so, just how big a loan to offer) include:

What stage is the company?

How big a round is the firm raising?

Most debt facilities I’ve heard of are sized as a function of the equity commitment

Who is investing in the equity?

Are they known for following on?

Aside from the first question, most of these are not things that equity investors I’ve spoken with claim to care much about.

Relative Risk

I view venture debt as just as risky as raising an equity round from VCs for founders and employees. Both types of transactions introduce investors with a claim on the value of the firm senior to the founders and employees, meaning the exit amount required to return cash to founders increases.

Furthermore, in either case, founders are betting the firm. Both equity holders and debt holders can force a sale of a company, and firm leaders have fiduciary duties to both types of investors.

However, there are some distinctions. If the firm fails to achieve its objectives in the fundraise, my impression is that debt holders will be quicker to force a liquidation or wind-up than equity holders.

On the other hand, if things are going well, those founders and early employees will benefit much more if they raise debt than equity, because after they pay back the loan all the projections of future revenue (and therefore value in the company, the way VCs think about it) are their own. They will become wealthier when they sell if it all works out.

If you invest in startups, like my writing, and want to chat about possible career opportunities, don’t hesitate to be in touch. The best way to get ahold of me is via email:

Example

Consider a startup. Just for fun, let’s say it builds AI for humanoid robots.

Before fundraising, the founders own 90% of the equity, and allocate a 10% employee equity pool.

The founders raised a $2 million priced seed round on an $18 million pre-money valuation. This is convertible preferred stock with a 1x liquidation preference, so when the company sells, the investors can either claim $2 million back or (assuming no further dilution) convert to common stock and take 10% of the proceeds distributed to the common stock.

The founders plan to raise an $8 million Series A on a $40 million pre-money valuation. The key question in this example is whether the founders will be better off raising money by selling only equity or half equity and half debt from two different funds?

The founders raise the round (assuming for simplicity the equity is convertible preferred stock with a 1x liquidation preference) and sell the company one year later, before paying down any of the debt’s principal.

Say the startup is acquired for $30 million — which is a bad outcome for all the investors.

Here, the Series A investor takes their liquidation preference in both cases, and the seed investor converts to common in both cases. There’s no difference to the founders and employees between the equity-only and the equity and debt cases.

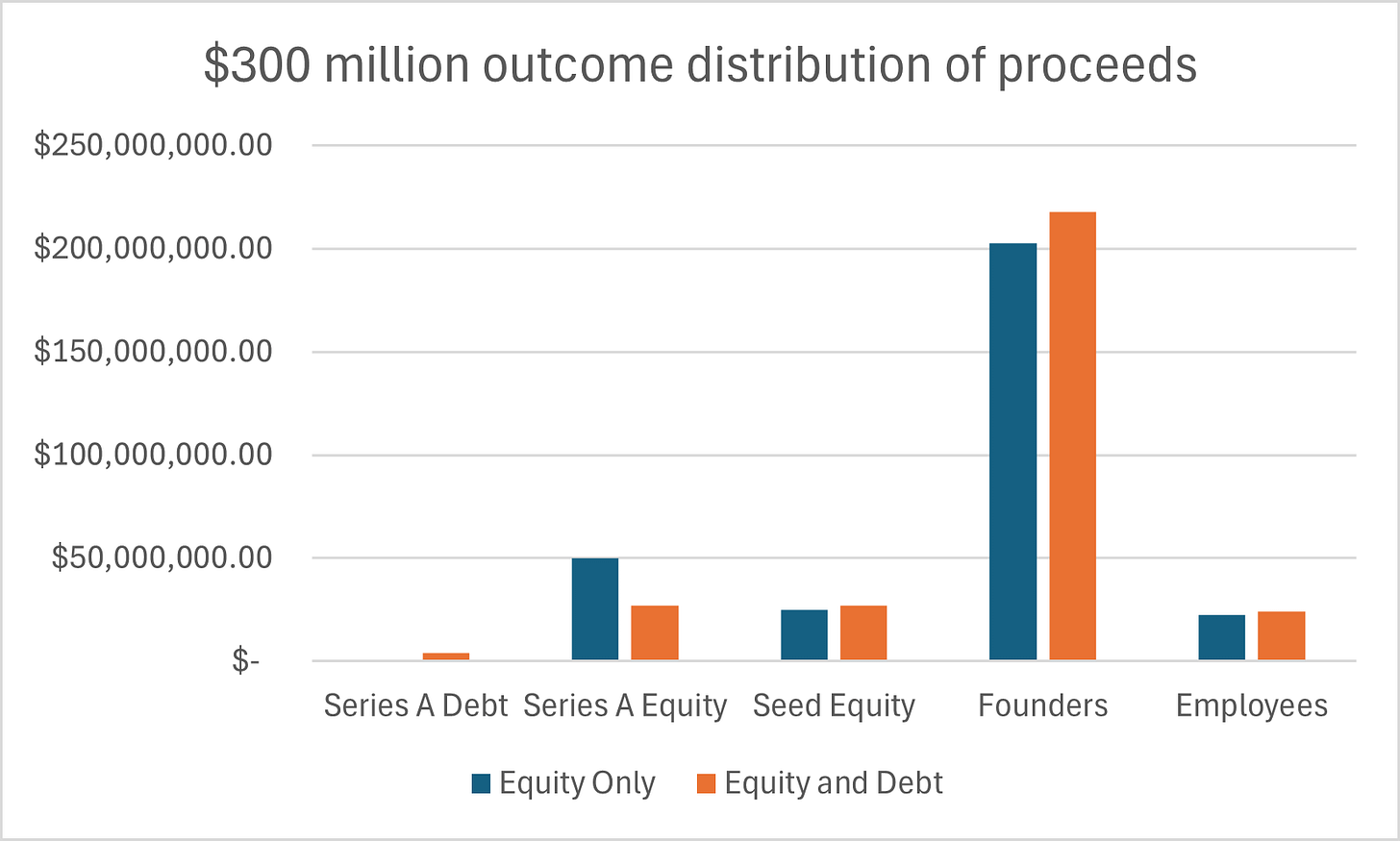

On the other hand, let’s say the startup is acquired for $300 million — which is a great outcome in terms of IRR and MOIC for pretty much everybody except maybe the seed investor.

This is such a great outcome that everybody who can converts to common stock to share in the proceeds. This has implications for all the equity investors, the founders, and the employees:

The Series A equity investor walks away with $50 million if the Series A was equity-only, or $26.9 million if the round was a mix. However, their IRR and MOIC look slightly better if the round was a mix (26.9/4 > 50/8 with time held constant).

The seed investor walks away with $25 million if the Series A was equity only, or $26.9 if the round was a mix. Their IRR and MOIC will both be better if the round was a mix, because the exit amount is larger in this case and neither time nor entry price are variable.

The founders get a $202.5 million payday if the round was equity only, or $217.96 if the round was a mix. Debt increases their outcome by nearly $15.5 million.

The employees collectively get a $22.5 million payday if the round was equity only, or a $24.2 million outcome if the round was a mix. Debt increases their outcome by $1.7 million.

Consider the Counterfactual

Due to attrition rates by stage, venture debt is not an option for most startups.

Furthermore, just because a firm can take on leverage, it doesn’t mean it should. I am not some MBA student telling companies to always lever up — that’s likely the wrong decision for most startups.

Some rock-solid reasons to not raise debt include:

not needing it for the startup’s operational plan

uncertainty in the operational plan’s timeline

lack of confidence in the startup’s valuation

founders want to see their underlying technology or concept persist regardless of how well the startup is doing over the medium-term

Wrapping Up

Venture debt’s ability to magnify returns for common shareholders is interesting.

It seems to me like it might be a good way to take advantage of a real valuation premium while reducing dilution for shareholders of common stock, if all the following conditions are present:

a well-understood function that relates returns and a specific use of capital

a premium valuation of the startup

confidence that the premium valuation is justified

I wish I had more data about how popular this approach to raising capital is in AI — and what’s driving its use. That’s what I feel like I’m missing to answer my questions about the relationship between the field and the financing strategy.

Mezzanine financing is to debt what preferred stock is to common stock. Mezzanine debt sits closer to the middle of the preference stack, after senior debt and secured debt and above all the equity — just like preferred stock sits above the common stock in the preference stack.