Y Combinator recently ran their Summer 2024 Demo Day. This semiannual (soon to be quarterly) event generates a lot of news in the startup world.

Accelerator programs like YC are just a small part of the venture capital landscape available to founders.

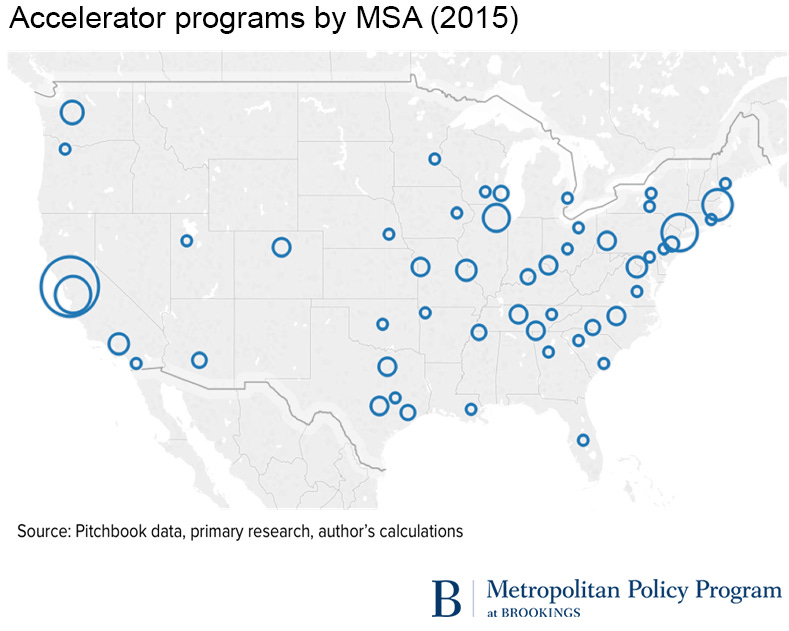

Accelerators are not just an important part of the American entrepreneurial ecosystem; they are a critical component at the earliest stages.

Accelerators play a role complementary to angels in that they provide early resources and connections.

While angels often have a hyperspecific value proposition to a startup that makes them a compelling addition to the cap table, accelerator programs are frequently more generalist, and support many startups at a time.

Accelerators are essential to VC-backed entrepreneurial ecosystems because they:

help many founders at a time

are a great place for first-time founders to learn

provide founders with initial funding

have signaling value to some VCs

There is a compelling argument that the accelerator environment in particular has been a key driver of the Bay Area in particular as a continued hub for entrepreneurial innovation over the past 20 years.

Accelerators also have a couple key costs that are worth keeping in mind.

Equity

The first, and perhaps more obvious cost, is the equity stake accelerators take in the startups they support.

Silicon Valley Bank, which partners with Techstars, put out an awesome podcast/article on the mechanics of startup accelerators.

It draws a distinction between university-affiliated programs, corporate programs, and pure-play financial programs that raise capital. Most accelerators, except for some run by non-profits, do take equity in exchange for a (typically very) small investment in the startup.

SVB says it’s common to sell 5-10% of the equity to an accelerator. The accelerators I checked for this all fall within that range. They also have varying deal structures. Here’s just a few of them:

YC, for example, takes 7% plus a variable amount using an uncapped post-money SAFE with a Most Favored Nation clause.1

Techstars takes 6% in common stock and offers a convertible note which founders are not obligated to take.

Neo, an accelerator I’ve been hearing about more and more recently, takes 6% using an uncapped SAFE with a $10MM floor. They are additionally entitled to buy 1.5% as common stock at the founder purchase price.

Beyond the different amounts of equity, the money accelerators invest and the structures of the investment also vary significantly between programs.

This makes it difficult for founders, especially those who are new to the world of startup financings, to compare their options.

I think that’s bad for founders.

It’s also somewhat worrying how much equity founders might be giving up for so little capital. There’s two reasons for this.

First, it means that the founders have a relatively small amount of money with which to hit a milestone that enables them to raise their next round.

Second, investors at various stages of the startup lifecycle often have ownership targets.

When founders sell too much of their company too early, the capitalization table of a startup can become unattractive to VCs; one reason for this is that they view founders and management teams as less incentivized when they own a smaller fraction of the equity. This isn’t an issue that’s unique to accelerators, though it is something that accelerator participants and alumni sometimes encounter.

Selling too much equity too early has killed startups in the past.

I don’t see that changing in the future.

Time

Participating in an accelerator program is an experience that also costs time. From the outside looking in and thinking like a founder, this currency seems more important than equity.

There’s a clock of sorts with a new venture to spin up interest among early-stage investors.

Participating in an accelerator not only starts the clock, but runs some of the time on it.

Now, accelerators will often compensate founders for that time by helping them generate VC and angel interest. Founders frequently get access to a platform like a demo day where they can pitch to more investors than they’d otherwise be able to, and that sometimes works out really well for them!

But more than the hours devoted to the programming itself, it’s also a question of time allocation outside of events. Accelerators will enthusiastically and repeatedly tell their founders to do certain things.

If the generally correct advice isn’t applicable to a specific founder who listens to it, they could be hurt by allocating time to what are basically the wrong tasks.

There’s some level of survivorship bias here in that the accelerators that survive are by and large telling most founders to do the right thing.

As a result, the risk founders take isn’t so much that the advice is bad, but rather that they’re an exception to the rule.

Accelerators have ways of mitigating this, but being one of many participants in a program at a time necessarily results in less individualized attention than a founder might receive from an angel investor, or even an early-stage VC.

Some accelerators address this by running smaller cohorts more frequently.

So, are they worth it?

I view this as a question better suited for founders, not for investors.

I would encourage first-time founders who get into a reputable one to consider it seriously.

If I saw a repeat founder had decided to participate in an accelerator on their current venture, I’d be very interested in learning about why they made that decision.

I keep on coming back to YC not because I have a particular position towards them, but because their terms and conditions are uniform, public, and relatively clearly explained. The link to their terms also has a good example of their practical effects, which makes them easier for people new to the world of startup finance to understand.