Months of Moonshots

I’m not such a fan of writing about news. I’m not trained as journalist, and both the investing and space worlds have some darn good ones. But both the past month and this coming month have momentous events in commercializing the space around the moon (cislunar space) that warrant some sort of comment.

On 8 January 2024, America’s first commercial lunar lander took flight. It was a remarkable flight of firsts — this Peregrine lander was the first piece of hardware by Astrobotic to fly to space, as well as the first flight of both the launch vehicle and its first stage engines. Even though the mission was unsuccessful, this marks in my mind the expansion of the commercial space age from cislunar space to the lunar surface itself.

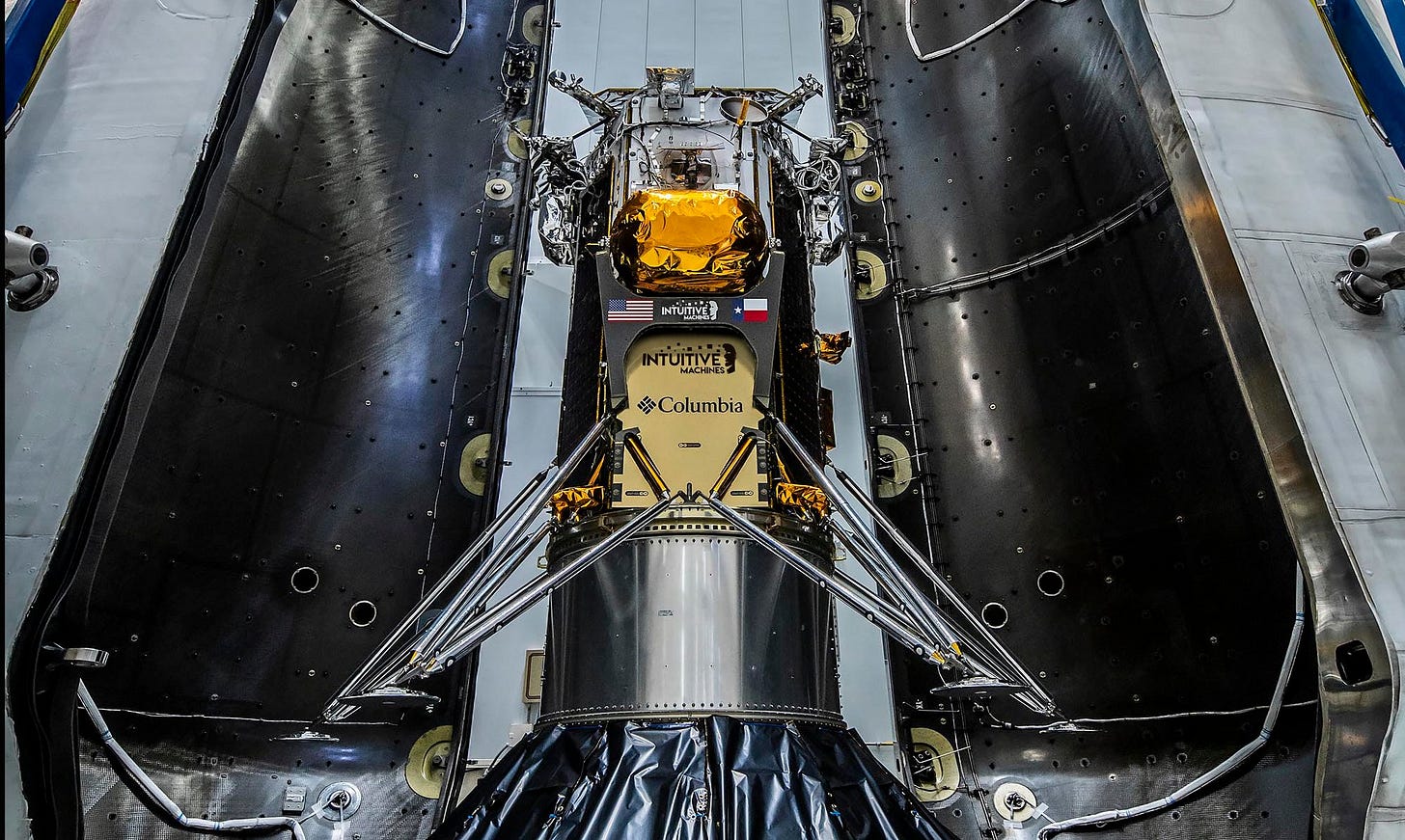

Another commercial lunar lander is scheduled to lift off on 14 February. This one, named Odysseus by a college friend of mine, is also the first flight of a firm called Intuitive Machines.

Both Astrobotic and Intuitive Machines are operating under commercial contracts from NASA through the Commercial Lunar Payload Services (CLPS) initiative. In both cases, I’m particularly interested in how the events impacted (or will impact) key participants; we’ll look at four firms across the two missions today:1

Astrobotic

United Launch Alliance (ULA)

Blue Origin

Intuitive Machines

Astrobotic

Astrobotic’s Peregrine lunar lander separated from the launch vehicle upper stage at the appropriate time, and powered on for checkouts en route to the Moon. Several hours into the mission, Astrobotic announced the vehicle had experienced a propellant leak that was keeping the vehicle from maintaining an orientation that exposed the solar panels to sunlight (without which the spacecraft could not function). The firm shifted their mission objectives to the vehicle surviving as long as possible, collecting as much data from the vehicle and its payloads as possible, and eventually performing a destructive re-entry over the South Pacific.

Amidst a really challenging operational situation, and absolutely heroic engineering efforts, I was struck by Astrobotic’s commitment to clear and timely communication. Over the course of the ten day mission, they posted twenty-two updates on social media, from X to LinkedIn. The updates weren’t just “we’re working on it”; they provided substantial detail about the condition of the spacecraft and the operations team’s intentions during a dynamic situation. They also shared some data and images from the lander.

Beyond their outstanding corporate communications, they also focused their efforts on two things that I believe are really important to the future of the industry:

Creating as much value for customers as possible The firm decided to run what payloads it could to generate as much scientific value as possible; the mission operations and anomaly response also created a lot of engineering value. Focusing on customer value creation when things go wrong is really important to convincing potential commercial clients outside the space industry that going to space is a worthwhile investment.

Socially responsible flight operations When it became apparent that the lander wasn’t going to land on the Moon, but had power to return to Earth, Astrobotic intentionally ended the mission earlier than they could have, by planning and executing a controlled, destructive entry that minimized risks to people on the ground and other satellites in space.

Astrobotic has opened an investigation into the anomaly, and it needs to be concluded before business impacts can be assessed responsibly.

United Launch Alliance

Astrobotic’s lander launched on top of a new rocket made by the United Launch Alliance called Vulcan, shown below on the launch pad.

Launching a new rocket for the first time is a tricky thing according to Tory Bruno, the CEO of ULA. First flights frequently don’t go exactly as planed. Even more frequently, there’s something that goes wrong during the final preparations for an initial launch that causes a lengthy delay in the process.

Vulcan…didn’t have any of that, which is downright remarkable. The rocket launched during its first opportunity after its arrival at the launch pad for launch (it had previously been rolled out to the pad for checkouts). This becomes common once a firm is experienced with a rocket, but typically not until then.

That’s really impressive to me, because with Vulcan, ULA took an approach to development that hasn’t really been seen since before ULA was challenged in the launch market by SpaceX in the 2000s. When SpaceX showed up in the mid-2000s, it and its followers like Rocket Lab and Firefly started from a clean sheet, redesigning everything from scratch.

It used to be when they needed more power on a rocket, they’d basically slap an additional motor on top or underneath, hyphenate the name, and call it a day (Thor-Able and Atlas-Agena are just two of many examples). ULA’s development process for Vulcan mimicked this, flying new components, like solid rocket motors, on flights of its existing rockets — Atlas V and Delta IV — before flying Vulcan for the first time last month. The Vulcan launch campaign shows that it is still technically possible to build something new using iterative development.

The key remaining issue is whether this particular design is commercially competitive against SpaceX and other operators in the medium-lift and heavy-lift launch markets. This is a pressing question for ULA, because it is a joint venture between Lockheed Martin and Boeing; its owners are reportedly looking to sell the firm.

Demonstrating their new rocket works and is far along the path to certification for national security space launches, which has been ULA’s bread and butter for the past decade, will go a long way to validating to potential buyers that the firm continues to have value.

Blue Origin

Blue Origin manufactures the BE-4 engines that power the first stage of ULA’s Vulcan rocket; this was their first flight. As far as we know, the engines performed flawlessly.

This matters, because Blue Origin has had some pretty serious challenges building and validating these engines. That shouldn’t come as a particular surprise, since they are the first American engines to fly on a launch to orbit with their particular fuel/oxidizer combination (Methane/Liquid Oxygen, or methalox), and cryogenic engine R&D is a very difficult engineering problem. The engines flew for the first time several years late, but they worked as promised.

The unique blue exhaust from the methalox engines, captured in this long-duration exposure below, was absolutely beautiful!

Everything about the smoothness of the flight that I said about ULA applies to Blue Origin as well. Their hard work building and testing this flight hardware paid off.

Blue Origin is a unique firm in the space industry because how it gets its capital. The overwhelming majority of the firm’s funding comes from Jeff Bezos, though it has flown space tourism missions, and has started to take on contracts to supply hardware to organizations like ULA and NASA.

What this mission means for the company in the near term is rather difficult to say. They have a unique corporate structure, eschew publicity, and recently swapped out their CEO. All these things make it tricky to anticipate their next actions.

Over the long term, the path forward is significantly more clear. This flight represents the opening of the hardware supply revenue stream. More importantly, it validates the technology underpinning their strategy for the next decade or so. Blue Origin is working on lunar landers and orbital transfer vehicles, but they can’t do any of that without cheap and reliable access to space. For that to happen, they need these engines to work, not just on ULA’s new rocket, but also on their New Glenn launch vehicle.

Intuitive Machines

What’s happened here? Nothing yet…but hopefully good things are coming later this month!

Intuitive Machines now has a shot at being the first non-government lander to soft land on the Moon, the first methalox lander to soft land on the moon, and the first lander built and operated by a publicly traded firm to soft land on the moon. The launch is planned for just after midnight (Eastern time) on Valentine’s Day.

This is the only firm in this list that’s a publicly traded company; Intuitive Machines went public via a special-purpose acquisition corporation (SPAC) in early 2023, and now trades on the Nasdaq exchange with the ticker LUNR. The SPAC itself IPO’d at $10, which is the industry standard, in in 2021. The stock ended trading on Tuesday at $3.62 per share; this is above the average for its peer space SPACs.

The market hasn’t been kind to these companies, so I’m not optimistic about what anything less than unequivocal success in this mission could mean for their stock value. I expect the market will be hypersensitive to any sort of anomaly announced during the mission, and I see it as really important to the firm that it succeeds here.2

I wish them luck.

Both privately and public space companies are starting to take the r/wallstreetbets saying “to the moon!” rather literally. That’s a risky thing in general, and particularly for firms listed on public exchanges, for two reasons.

The path from exploration to commercialization on other moons and planets is not clear. It’s not even clear at this point that it’s possible for a young company to turn a profit in Low Earth Orbit — and landers have far higher R&D requirements. There’s not just substantial technical risk here, there’s major financial risks as well.

Most equity owners are not rocket scientists. They don’t really understand the different ways missions can go right or wrong, and what that might mean for a startup — they can (and do) just trade on press releases that ultimately say “success” or “failure”.

Cislunar space may be open for business, but nobody — from university spin-offs like Astrobotic to behemoths like Blue Origin — has shown yet that it’s possible to make a profit landing on the Moon.

Personally, I’m excited to see that change!

An important point that should contextualize my assessment of both Astrobotic and Intuitive Machines is that nobody — no company, nor NASA, nor JAXA, nor anybody else — has successfully soft landed on the Moon on their first visit to cislunar space.

This is not investment advice.