MOIC & Me

VC performance on this Substack & the metrics I'm not using as much

I’ve realized that in my writing about venture capital as an industry on this Substack, I’ve emphasized MOIC as a key metric a few times. It’s worth sharing why I’ve made that decision, and what the alternatives to it are.

I’m aware of three different performance metrics that Limited Partners use to evaluate VC funds:

Internal Rate of Return (IRR)

Multiple On Invested Capital (MOIC)

Public Market Equivalent (PME)

Interestingly, Carta looks at IRR and MOIC, but not PME.

WARNING: MATH AHEADAll of these metrics can be calculated gross or net of fees. Also, bigger numbers are better in every case.

IRR

Formula

NPV is the Net Present Value, which is the difference today between the present value of future cash inflows and outflows to the VC fund. What this means on a practical level is that the IRR formula is a special case of sorts of the NPV formula. NPVs are relatively common calculations in the financial world.

C looks at cash. C0 represents the cash outflow from the fund to the investment. Ct represents cash inflow from the investment to the fund.

t represents the number of time periods, with t=1 indicating the initial time. The equation is interested in the sum of the cashflows over defined time periods.

Mathematically speaking, the Internal Rate of Return is the discount rate that makes the Net Present Value of all future cashflows equal to 0 in a discounted cashflow.

We are fortunate to live in an age where there’s an Excel function for IRR calculation.

Key Drivers

Holding period

The discount rate reflects the time value of money, the idea that funds allocated to any project could be put to work elsewhere — so the sooner those funds are returned to their investors, the better.

IRRs particularly reward short holding periods, so IRRs at VC funds (which plan for holding periods on the order of 10 years) tend to be lower than similarly structured buyout funds, which plan to hold investments for about 5 years.

Recycling can impact this.

Cash outflows from the fund to the startup

This is the cost of the investment.

Cash inflows from the startup to the fund

This is the money the fund receives from an exit (acquisition/IPO) if the investment in the startup works out.

This could also include dividends.

The target user for all performance metrics is ultimately Limited Partners. Some LPs are high net worth individuals, and others are institutions.

Any institutional investor or fiduciary can calculate an IRR. This makes IRRs particularly useful for considering VC fund performance in contrast to other asset classes, like commodities, and buyout funds. This metric helps LPs figure out how much capital to allocate to VC as an asset class — and perhaps within it.

There are some recent perspectives out there that VC funds, as well as LPs, may be over-indexing on IRR as a performance metric during the fund lifetime.

Harris et al. calculated the average IRR of a VC fund is around 16% / year.

MOIC

Formula

Unrealized value is the value still tied up in investments.

Realized value is the value distributed back to investors already.

Capital invested is the initial investment.

This is similar, though not identical, to concept of TVPI — the ratio of the total (distributed and undistributed) value of the fund’s investments over the paid-in capital. The key distinction between them seems to be that TVPI only uses the capital that has been called by the fund for the calculation; they converge after all capital commitments have been called.

Key Drivers

Cash outflows from the fund to the startup

Cash inflows from the startup to the fund

This metric is totally insensitive to the holding period.

MOIC, as with all these metrics, is important to LPs. It’s important to note that analyzing MOIC the simplest metric here to both analyze and calculate.

MOIC > 1 means the investment made money. MOIC < 1 means the investment lost money.

Harris et al. say that the average MOIC of a VC fund is on the order of 2.36x.

PME

Formula

The formula invites us to consider a counterfactual: what if the money allocated to a private equity fund (or investment) was instead allocated to buy a stock index on that date, and then sold on the same date the VC fund was returned?

In the paper where Kaplan and Schoar introduce the KS-PME, they provide a solid explanation in more words in the first paragraph of Section III A, “Private Equity Performance”.

Key Drivers

Choice of index

Which index is used is going to have a massive effect — indexes can be designed to emphasize different characteristics of equities.

Holding period

Investments in public markets for longer times tend to have less volatility, resulting in a more consistent PME.

Entry and exit timing

While IRR looks at the holding period as a driver, PME compares two different investments’ performance over a specific time period.

The same investment in the second half of the 2010s and the first half of the 2020s, at the same entry and exit prices, would have a different PME if the index used performed differently.

Entry price

Exit price

PME > 1 means the private opportunity outperformed the index. PME < 1 means the private opportunity performed worse than the index.

Harris et al. suggest that the average PME of a VC fund is on the order of 1.29x.

Example

Instead of working examples at the fund level, we’ll consider individual investments in this set of examples.

Consider a notional VC fund that invests in four startups, compared with the S&P 500.

Startup A received a $100 investment from the fund in 2020, and returned $400 to the fund in 2023.

Startup B received a $100 investment from the fund in 2020, and returned $400 to the fund in 2022.

Startup C received a $100 investment in 2021, and returned $400 to the fund in 2024.

Startup D received a $100 investment in 2021, and returned $200 to the fund in 2024.

One does not typically invest directly in the S&P 500, but gets exposure to an index through a mutual fund or ETF that tracks the index. VOO, Vanguard’s ETF product that tracks the S&P 500 in its asset allocation, closed at $236/share on March 31, 2020; $364/share on March 31, 2021; $415/share on March 31, 2022; $376/share on March 31, 2023; and $480/share on March 31, 2024.1 I pulled data from Nasdaq.

To simplify the math, during the term of each investment, there is no cash out from any investment, and the returns encompass all cash to which the fund is entitled.

We’ll use these six possible investments, with these values, throughout the example, and assume all transactions happen on March 31st.

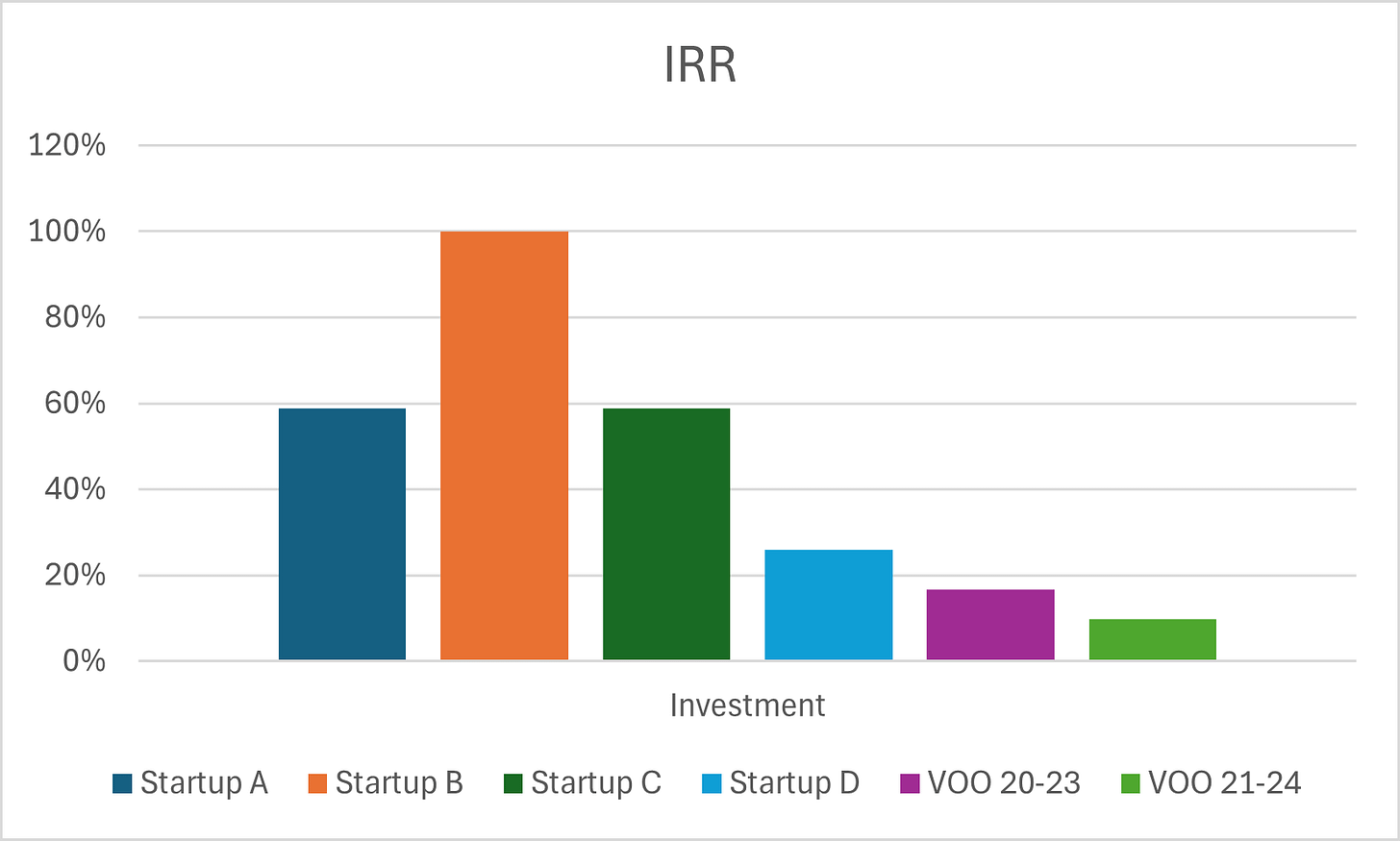

IRR

Here are the IRRs.

Comparing the IRR of Startup A with Startup B illustrates the positive impacts of a faster exit to this metric, holding the exit price constant.

Comparing the IRR of Startup C with Startup D illustrates the importance of exit price to this metric — Startup D returned half of what Startup C did over the same holding period, but Startup C’s IRR is more than twice that of Startup D.

The same impact exists for entry prices; price sensitivity in the initial investment has a major impact on IRRs.

This is one reason that investors might be particularly sensitive about anti-dilution protections and MFN clauses in term sheet negotiations.

Startup A and Startup C have the same IRR; this metric doesn’t care when the investment was made, only how long it was held.

MOIC

Here are the MOICs.

All startup MOICs are identical, except for Startup D (which exited for half the price of Startups A, B, and C).

PME

Here are the PMEs.

Startup A had a better PME than Startup B not because it returned more dollars, but because the S&P 500 wasn’t doing so hot when the position in Startup B was sold.

Startup C and Startup D had the same holding period; because Startup C was sold for twice the amount of Startup D, Startup C’s PME is twice that of Startup D.

Startup A and Startup C had the same holding period, entry price, and exit price — but because the S&P 500 was valued differently on the days where the startups were bought and sold, they have different PMEs.

Only the startups have PMEs.

An investment in an index will always have a PME of 1 when compared to that index.

An investment in a publicly traded equity doesn’t need a public market equivalent.

Why I prefer MOIC here

MOIC is compelling to me as I write about early-stage investing because it’s not clear how long investments at this stage take to exit. I’m looking at things on a VC-scale timeframe (about 10 years), but the right opportunity to sell could come at 9, 11, or even 5 years after an investment. I’m also not an expert in the public markets. Framing things in terms of MOIC abstracts these things away when I’m developing perspectives on things like success at Series A.

MOIC is also relatively simple and easy to explain.

Unlike IRR, the math involved is a ratio, not a summation or exponential function. Unlike PME, I only need to track and explain one investment. Since I write here for a diverse audience, the relative simplicity of MOIC allows me to spend more time on the analysis of the numbers and opinions — as opposed to walking through equations.

I’m not opposed to using these other methods when they make more sense. I just haven’t found many times when they did yet.

That also doesn’t mean these things don’t impact how I think about the investment decisions I make — they very much do. Rather, they have a smaller impact on how I structure and justify my thoughts here.

I should disclose that I hold VOO in my personal portfolio.

Super thorough and easy to understand break down!