The space industry has two large verticals that are almost diametrically opposed in terms of design constraints:

Rockets have to work perfectly, but almost always have a design lifetime < 24 hrs

Satellites can encounter and recover from errors, but have to be able to do this repeatedly for years — sometimes even decades

I used to work with satellites, but I have to hand it to the rocket companies — they tend to have much better marketing, if for no other reason than rockets are cool. They have (usually) controlled explosions and inspiring visuals.

Marketing satellites and the data they provide is a different type of problem. Like rockets, it’s still typically a type of B2G or enterprise sales, and complicated by the fact that the user is often not the buyer. There’s lots of procurement through RFPs, which may or may not be open.

As a result, most marketing motions in this sector don’t happen in public view.

Umbra, a Series C startup founded in 2015, is an intriguing exception.

Synthetic Aperture Radar

Umbra is a remote sensing firm that specializes in synthetic aperture radar (SAR) data. They sell data their satellites capture, and are also happy to sell spacecraft.

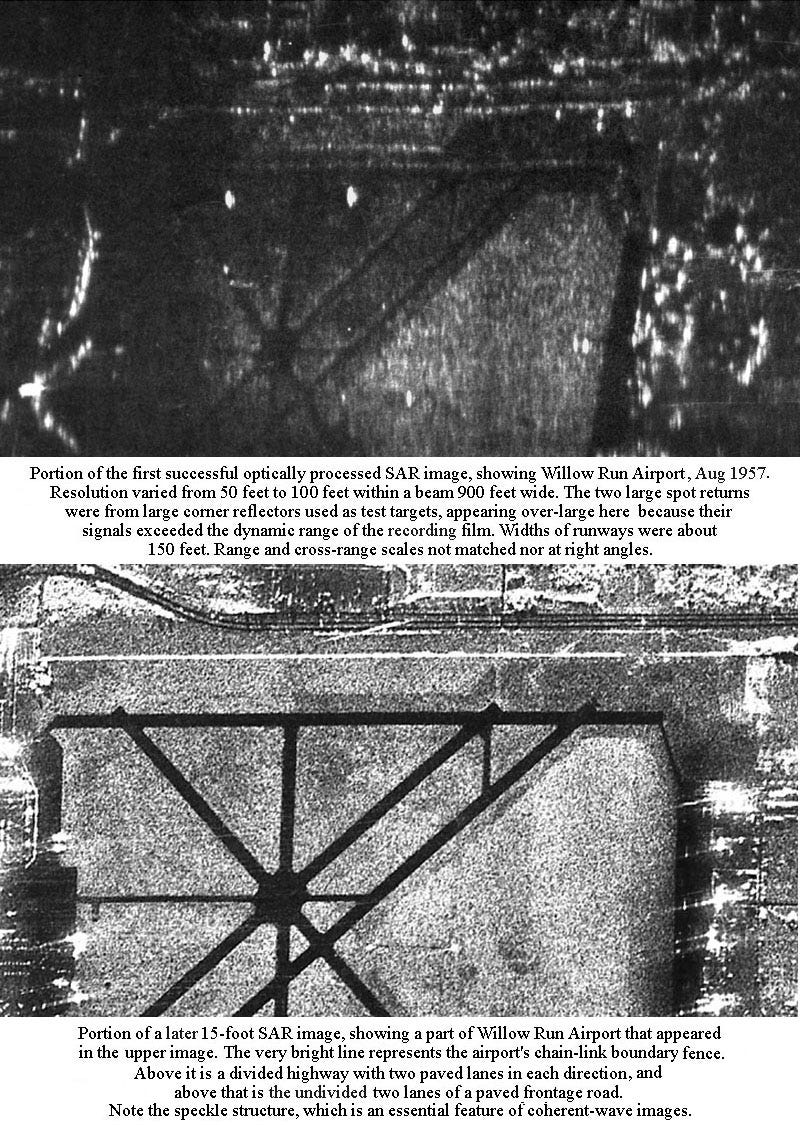

SAR uses a moving radar emitter to image a 3D object in 2D. The substance of it is that this allows an image to be taken from what looks like a much bigger aperture than is actually used.

To put it in more familiar terms, the effect is somewhat like the opposite of a police officer’s radar gun (instead of a static sensor tracking a moving target, a moving sensor tracks a basically static target) but expanded out from 1 dimension to 2.

The technology was originally developed for missile guidance back in the 1950s. It was particularly useful for this purpose because unlike the cameras on our phones, SAR is not affected by weather phenomena like rain, clouds, or nighttime. This made it useful for navigating — or tracking things — during periods of darkness or poor weather.

Since SAR was originally developed as classified technology for the military, the part of the population who knew how to analyze it used to be, for the most part, within the military.

This hampered its commercial development and exploitation until the last decade.

Umbra

Umbra is a relatively mature startup, which means their marketing motion has changed from “do things that don’t scale” to “do things that scale really well”.

This makes them worth looking at in the context of space companies with “unique sensors [that] will continue to create value on Earth”.

While they use satellites as their proprietary collection tool, Umbra is, at its core, a data-as-a-service business.

Many remote sensing data customers aren’t particularly familiar with SAR due to its military origins, so Umbra has developed accessible educational materials. The idea of providing educational materials to prospective customers is not unique, but the materials seem effective to me — as somebody who is interested in both satellites and software, but has not gone all that deep in the technology of SAR.

They’ve also got a more active social media presence than their competitors.

The firm and its leaders regularly share interesting, even unique, content on places like X. That’s important in making new customers aware of their products, and in building a brand — but again, it’s table stakes for most B2B data companies outside the space sector.

I think they’ve made 3 key decisions which together form a unique marketing strategy in the remote sensing data space:

Sharing data

Clear pricing

Avoiding analytics

Sharing data

Umbra is a pioneer in its making SAR data publicly available. This opens up its sales funnel, and potentially introduces new users to SAR as a type of data.

These activities fall within the scope of Umbra’s Open Data Program. The program has released over 3,000 images representing more than $4 million worth of data, which is available via AWS and SkyFi, a remote sensing data marketplace.

The more regular element of this program is about 20 targets they regularly image, and make all this data available for free under a Creative Commons License (CC BY 4.0). This allows prospective customers to get familiar with the idea of using time series analysis to identify changes in the imaging targets.

Umbra also tasks satellites and makes data available in response to emergencies under this program. It’s great to see space startups integrating marketing with the drive towards corporate social responsibility.

Clear pricing

Umbra was a leader in publicizing its pricing, and announced its intentions to do this when it emerged from stealth mode.

SAR data used to be functionally priceless — users needed a national security justification to get it. Then it became possible to buy on the commercial market by talking to sales reps. This made pricing data proprietary, which was a massive advantage to incumbents.

Umbra’s decision to make pricing information available to the general public by listing it on its website was probably the biggest innovation in terms of business landscape that SAR has seen since 2000. This changed industry dynamics because it created an incentive for the competition to be more open about their pricing.

Consequently, it forced legacy SAR data providers to consider competing on price, in addition to other technical specifications common in remote sensing, such as:

revisit rate (how often a satellite can see if something has changed)

image resolution (level of detail available)

types of data available (both in terms of file format and types of images captured)

In the short run, this part of their go-to-market strategy seems to have relied on undercutting legacy SAR data providers on price.

It worked!

It opened up some really interesting partnership opportunities for the startup.

This might be a double-edged sword over the long run though: it could be a massive advantage for Umbra, or, if it turns out that somebody else has a better sense of willingness to pay, it could move SAR pricing towards a race to the bottom. If that happens (though I don’t think it will), it’d be unfortunate for Umbra, and fantastic for the industry; it’d prove conclusively that SAR data is becoming commoditized.

Avoiding analytics

The third, and perhaps most important, thing Umbra does is promise not compete with its customers.

This is a big deal to me as an investor in the space, because a critical question I’m worrying about and seeing other VCs worry about in the context of remote sensing data analytics, is “what happens if the data vendor (satellite operator) extends into this space?”. That’d be particularly concerning if I was thinking about buying data from a satellite firm that describes itself as “vertically integrated” like Umbra.

By committing to not compete with their customers, Umbra increases the confidence that their buyers have in their ability to provide a unique value proposition to their own users/customers.

If I were a buyer of SAR data, this would have a massive impact on my procurement decision-making.