What's holding back Generative AI adoption at work?

And how do we fix it?

Last weekend, I read a court order from the Southern Division of the Northern District of Alabama’s U.S. District Court. It sanctioned attorneys at a law firm who used a Generative AI (GenAI) tool that hallucinated citations in a motion.

I read the fifty-one page document to see why the judge thought the use of the tool was problematic. The short version of it is that it’s inappropriate for a lawyer to misstate the law in their filings with a court.

Curiously, the firm that employed the sanctioned lawyers, Butler Snow, was not sanctioned. The judge could not find evidence that the firm either acted recklessly or in bad faith. Butler Snow was not sanctioned because it understood that GenAI tools are black boxes, and its policies reflected an appropriate lack of trust in processes its attorneys did not understand.

My sense is that Butler Snow is generally representative of large companies with responsible IT policies. They don’t like tools whose internal mechanics they do not understand.

This is hampering the professional adoption rate of AI.

Generative AI Adoption

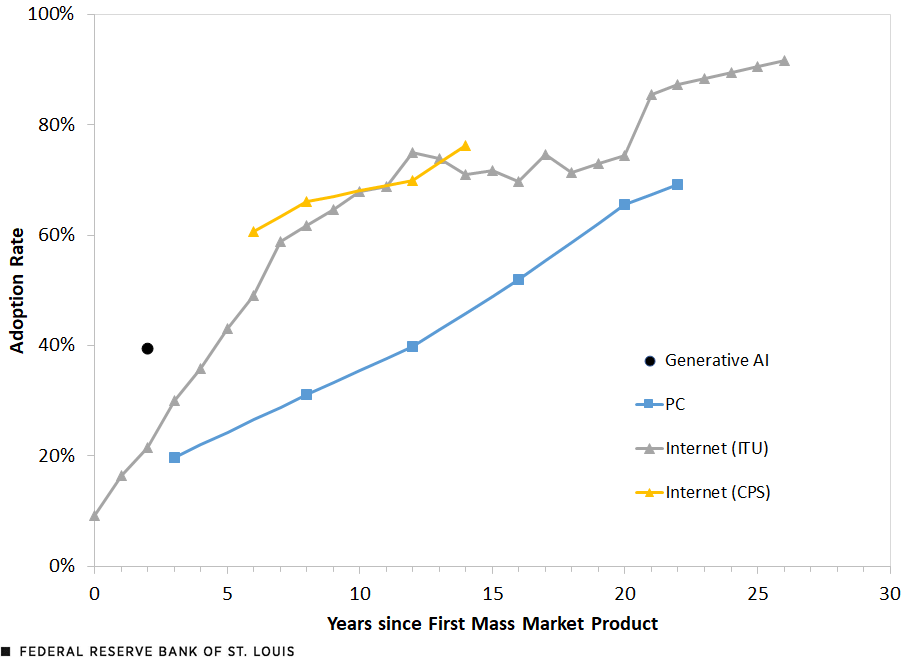

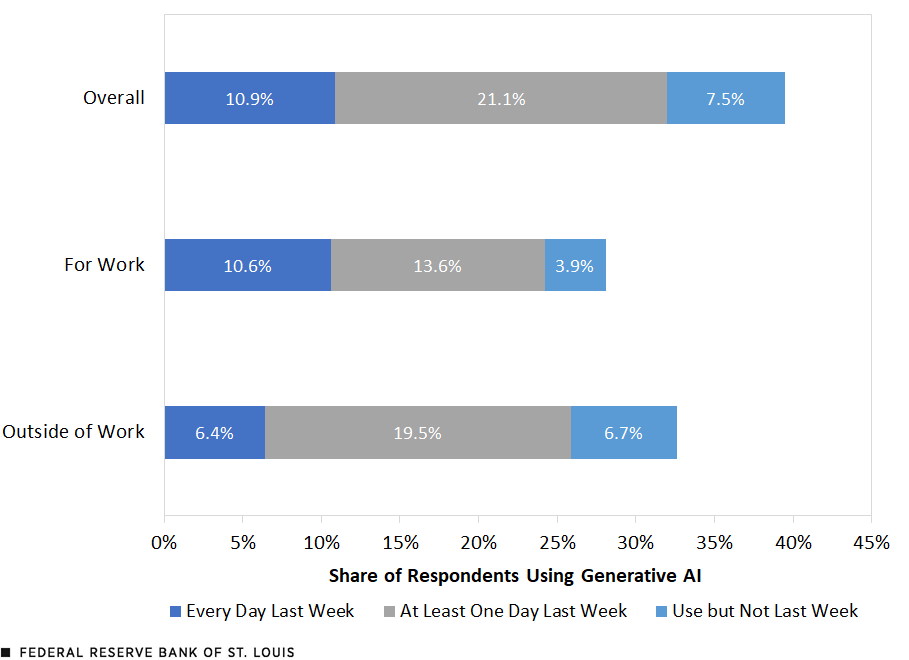

GenAI tools matter to the American economy. About a year ago, the Federal Reserve Bank of St Louis published a study about GenAI adoption in America. The results were eye-opening. GenAI adoption has been happening at a much more rapid pace than earlier IT innovations. Already, nearly 40% of Americans use GenAI technologies.

Diving deeper into the data, the Fed finds that interaction with GenAI in general is more common outside of work (32%) than at work (26%), daily use of GenAI is more common at work (10%) than outside of work (6%).

GenAI tools are used by about 28% of the American population at work, and of these, the plurality seem to use it at least weekly.

This is a large enough share of the North America geographic market that the reasons the remaining 72% of the workforce don’t use it are probably not technology-related.

Some significant portion of American workers likely can’t benefit from these tools. For example, I struggle to see how GenAI applications might make work easier for a barista or a welder.

But there’s a lot of opportunity here, particularly for white-collar jobs, and there’s got to be a reason so many other firms are taking a more cautious approach to adopting the technology.

IBM conducted a survey to understand the issue better and found five particularly popular reasons firms chose not to adopt AI. At least 40% of the survey respondents expressed worries about:

Bias or data accuracy

Lack of proprietary data

Lack of expertise with GenAI

Lack of business case

Data privacy

The second, third, and fourth issues are all really about the firm. A company probably needs to have a view on GenAI as it relates to talent, data, and financial outcomes in order to get great value out of the tool. At the same time, these are issues internal to the company.

The first and the fifth issue are about the AI tool. Moreover, they almost sound like concerns that might be raised about an employee’s trustworthiness.

Other institutions agree that AI has a trust problem, like the Harvard Business Review, KPMG, and academics everywhere from the University of Alabama to UT Austin and Stanford.

Observability Could Fix the Trust Problem

Trust is an intrinsic issue to GenAI because generative tools today are probabilistic.

Some models upon which GenAI tools have been built are open-source, though most of the leading Large Language Models are either proprietary or have licenses which are considered too restrictive to really be open-source.

This means it’s impossible to just open up most GenAI tools and watch them work to increase user trust in them.

However, there’s a whole branch of software development called observability that studies how software performs based on external indicators, called telemetry. Observability tools collect data about programs’ execution, internal states, and how various parts of the program communicate with each other. The information studied includes logs, which record events that happen in a computer system, traces, which record information about how code is executed, and data inputs and outputs of the program.

Observability tools make software services’ internal workings more explainable.

These concepts are applicable to GenAI systems too, in that telemetry from AI tools can help firms understand how probabilistic software behaves. This might include more traditional types of logs, as well as things like trace reasoning chains, hallucination metrics, input data quality, and model drift.

Because observability tools have the potential to make GenAI tools more explainable, they could mitigate the trust concerns which are adversely affecting GenAI adoption rates.

Estimating the Market Size

Top-down

In June 2025, Mordor Intelligence predicted a 15.9% CAGR in the global observability market through 2030. It assessed the market size was about $2.9 billion in 2025, and expect it to be around $6 billion in 2030. It sees North America as the largest region today, but expect most of the growth to come from the Asia Pacific geographic region. The firm noted that large enterprises comprise the majority of the market.

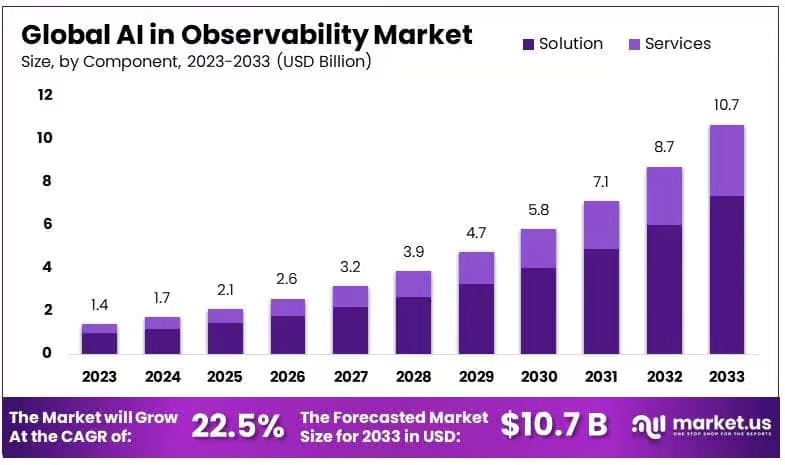

In December 2024, Market.us published an market report about AI in observability predicting a 22.5% CAGR through 2033. It concluded the market was worth $1.4 billion in 2023, and will be worth about $10.7 billion in 2033. One of the things it predicted, where there seems to be consensus, is that services will form a growing part of the observability market.

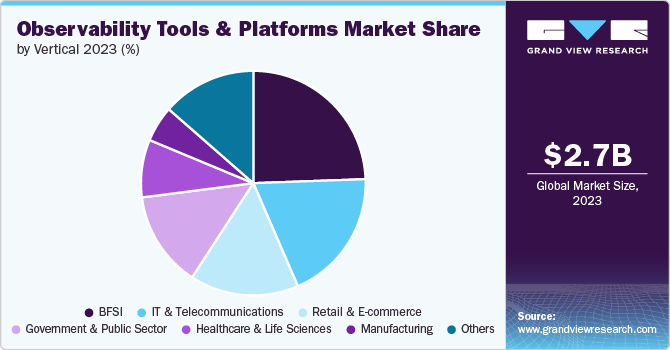

In 2024, Grand View Research published a report on observability. The firm forecasted a 10% CAGR from 2024 through 2030, with the market size starting at $2.9 billion in 2024 and finishing around $5.4 billion. It thinks finance was the biggest vertical in 2024, and thinks that retail and e-commerce will grow the fastest over the coming decade.

There’s disagreement about the specific growth rate, but all these reports agree that observability is a VC-scale space based on the market size. Furthermore, all these reports find that growth in the sector will be at least 3x the IMF’s expected global GDP growth rate over the remainder of the 2020s (which will be around 3%).

Curiously, not all the firms felt comfortable making predictions out to the ten year period I’m used to seeing in this sort of research. I interpret their refusal to make projections that far out an indicator of the growth expected in this vertical over the coming 5-15 years.

Bottom-up

Top-down market sizes establish the market size order of magnitude and growth rate, but bottom-up market sizing work tends to be a more accurate estimate of the market size this year.

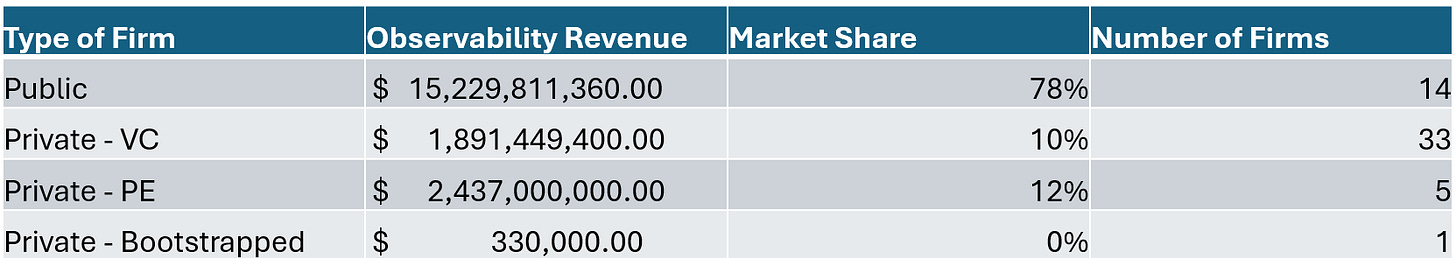

Last weekend, I put together a market size focused on observability in AI. I looked at nearly 80 companies that are or were building in the space. At the end of the day, I found 53 companies that appeared to be generating material revenue in the space. Defining the market size as the revenue, I found the market is about $19.5 billion.

Market participants had a variety of capital structures.

Public companies command the majority of the market, which makes sense because they’re the biggest firms around. It was difficult to see just how revenue from GenAI observability impacted the firms’ 10-K filings, so I made some judgment calls to estimate what small (low single digit) percentage of cloud revenue was attributable to AI-compatible observability tools.

Venture Capital-backed firms command about 10% of the market, and there’s about 33 of them. I made no effort to distinguish between early-stage and late-stage companies in the table above, because my data collection made clear that the late-stage companies had much more market share than early-stage companies.

Private Equity-backed companies are about 12% of the market, and tend to have somewhat less revenue than publicly traded firms. While this segment commands more ownership than the VC-backed segment, there are only five companies in this segment of the market, which probably reflects a couple dynamics:

this space is relatively new, so only PE firms that are open to newer fields will invest in the space

SaaS company revenue is not always particularly sticky, which could make PE firms more hesitant to enter into the space

PE-backed firms are bigger than VC-backed firms

The first two points borne out by the owners of the companies. Of the five, three are owned by Francisco Partners and Vista Equity, which both built reputations as technology sector experts.

It is possible to bootstrap in this space, though I only found one company that did so and was still operating, and its market share was a rounding error.

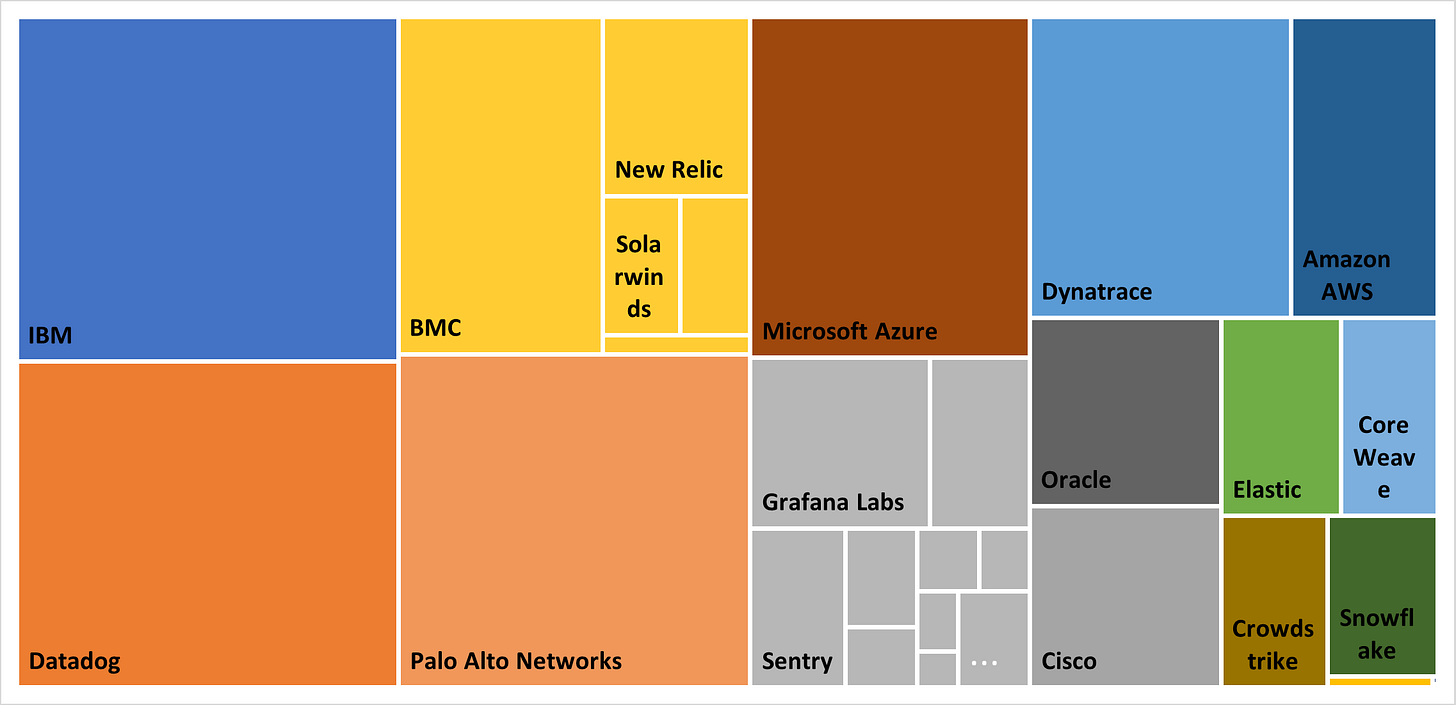

The treemap chart below shows the market leaders.

One thing my graphic shows is that the market doesn’t have a clear leader. The competition in this sector is wide open.

Another important observation here is that most of these publicly traded firms entered the market through inorganic growth, by buying other companies. Particularly notable transactions include:

This is exciting because it shows there are buyers for successful startups in the space that can craft a narrative of strategic alignment with a large company.

Looking at the publicly traded and VC-backed firms, another critical observation is that lots of the firms do AI observability and something else. This might mean that the pure-play winner has yet to become apparent. It might also mean that AI observability is mostly important as part of a platform.

The other important element of this treemap is who isn’t on it. LLM-driven firms like OpenAI and Perplexity don’t appear at all. This is on some level intuitive because observability tools are not very likely to improve the reputation of model companies. It means that the model companies are unlikely to expand into this space, which is good for startups in the sector.

Alternative Approach

My revenue number was larger than expected, so I searched for another estimate to check my work.

Mirko Novakovic, a second-time founder in the Observability space, put together a blog post with his estimate of the market size in December 2024. He got a bottom-up estimate of $12 billion in 2024, and an annual growth rate of 20%. He did a self-check that sized the observability market as a function of cloud software spending, and concluded a fair top-down market size estimate is $40-50 billion.

A lot has changed in the AI sector over the past eight months, and my number is smaller than his top-down estimate, so I’m comfortable with my bottom-up estimate being somewhat larger than his.

Wrapping Up

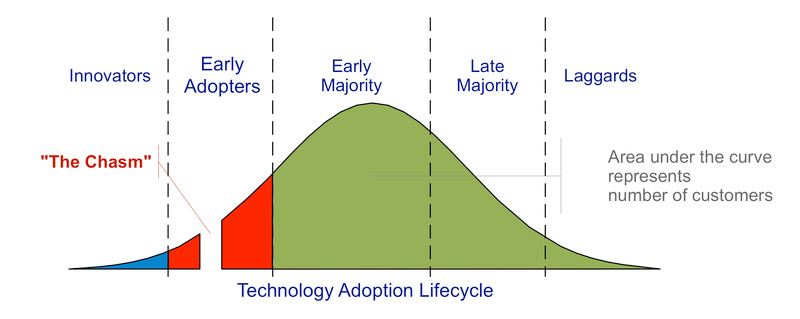

GenAI has crossed the chasm into “early majority” adoption.

Adoption rates are not moving faster because AI tools are black boxes, and firms are often unwilling to entrust critical work to a black box.

AI observability tools can address these concerns by making the AI more explainable.

Giving humans the agency to accept or reject an AI’s work after seeing it explain itself treats the AI more like a human; this is a step-change in how we relate to AI.