My initial exposure to VC investing has been at Dorm Room Fund, which is a generalist fund. However, my professional experience is in the space industry, and the opportunities I’ve seen and gotten the most excited at DRF about have all been in a different sector. This has me pondering the merits of generalist investing, as opposed to focusing on a specific sector.

It’s pretty clear to me that industry cycles (like the internet in the late 1990s, and mobile in the early 2010s) impact all types of investing, including VC. For VC in particular, I’d expect to see more deals in these growing industries, a higher percentage of funds getting VC backing, and a higher entry price.

This last point is a particularly important consideration for venture investors. Higher entry prices drive down returns when expressed as a multiple on invested capital.

Not only do industry hype cycles impact entry prices, but even for sectors that aren’t the present investing fad, the underlying industry also plays a massive role in how the ongoing expenditures of an investment are organized — which impacts if/when and how it will need to raise more money.

For example, manufacturers need large capital expenditures at the start for production facilities, SaaS firms tend to have higher operational expenditures on servers and developers, and hardware-as-a-service providers need unusually large reserves for maintenance. This has a significant impact on a firm’s capital needs after the initial check, which investors need to keep in mind because of their pacing and reserves strategies.

Furthermore, the underlying industry has a massive impact on exit events, where a company is frequently valued as a multiple of revenue.

As a result, and as the plot above shows, VC funding is not allocated equally across sectors.

Why might sector-specific investing be better?

Sector-specific investors focus on one particular kind of company, which is itself very much a spectrum.

On the broader end, some funds focus broadly on “deep tech”, or “near frontier tech”, which I understand as startups that rely on scientific or engineering innovation — regardless of the field of the innovation.

Then there are funds that focus on specific sectors of the economy. Defense tech is having a moment right now, and climate tech has been perennially popular on at least some level since the early 2000s.

It’s possible to get even more specific than that, and look at key elements within economic sectors. I know multiple investors who only look at deals relating to space, for example. Drug discovery and food tech are other niche technical fields that attract specialized venture capital investors.

Investing within a specific sector is potentially compelling because it allows investors to develop a deeper understanding of the industry, and opportunities within it.

It also allows the development of closer relationships with strategic investors within the industry, creating real network effects.

Perhaps the most interesting thing about this is that it appears to enable an investor with a smaller network. If an investor knows all the people in the field, that should be sufficient.

But that’s not actually true — if a VC isn’t paying attention to people building in other spaces, they risk getting caught out of position when a founder with a background in a different sector enters the playing field.

Why might generalist investing be better?

The other approach is to find the best deals in every sector, and there’s lots of sectors to choose from.

In theory, and handwaving away the issue of access to deals, this allows an investor to pick the best of every sector. As a result, one might think that a skilled generalist investor should outperform an equally skilled sector-specific investor.

Furthermore, this broad, generalist understanding of what “great” startups look like across sectors ought to give a generalist investor a better understanding of the relationships between sectors. I think this should help them identify opportunities at the interfaces between sectors.

It’s also possible to view industry concentration as a bad thing; if founders were to stop creating edtech startups, and my fund’s investment brief was edtech…I’d have a problem. Generalists don’t have this risk.

What does the data show?

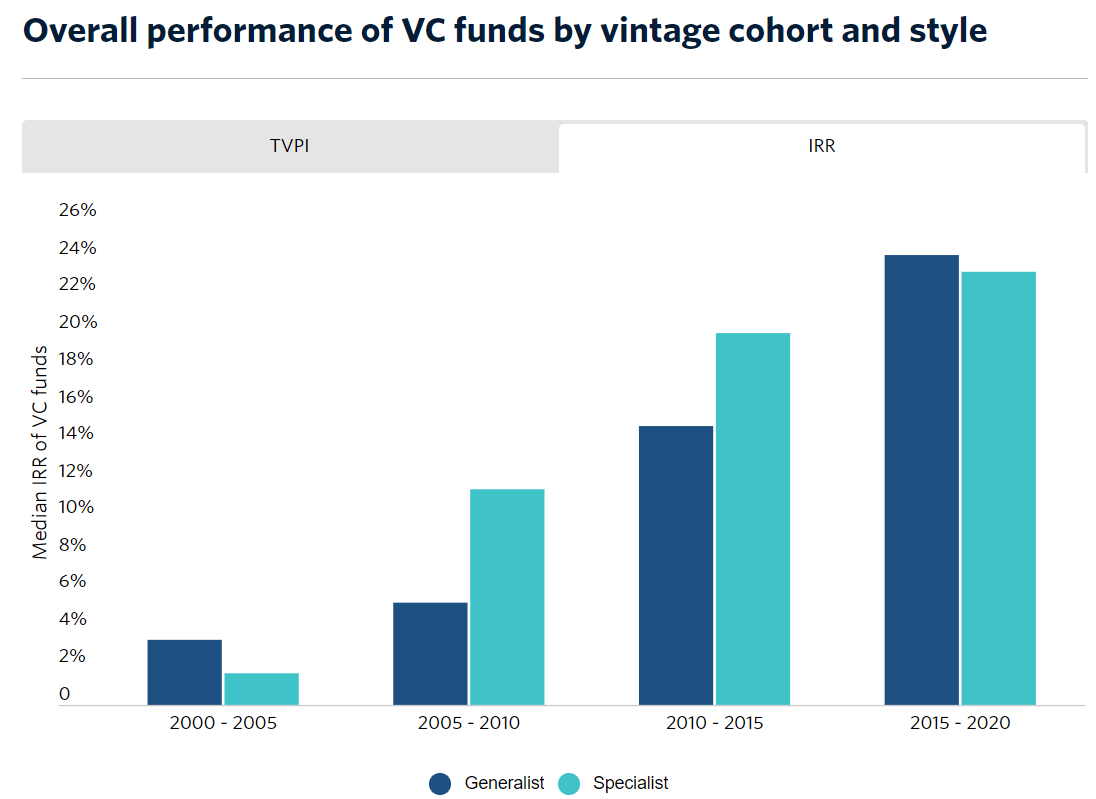

Pitchbook showed the two types of investors as very close, at least in terms of IRR.

For the past five investing years for which data is available, generalist funds have been outperforming across all fund sizes.

But among small funds, specialists appear to have an edge — and not a particularly small one either.

I don’t know why this is happening.

My best guess is that first-time investors typically raise small funds, and industry network effects are most pronounced at the point in an investor’s career when somebody makes the switch from founder/operator to investor. This should benefit sector-specific investors more than generalists.

Granted, all of this is backwards-looking data, and particularly in VC, there’s no guarantee at all that the past predicts future performance.

In fact, that’s part of what makes venture investing so compelling to me. This idea that what’s worked so well in the past might work in the future — but isn’t going to lead to those power law type returns — is essential to understanding how investors think about and evaluate startups.

I find meaning in searching for and supporting awesome people who are creating new things which will change customers’ lives in ways that nobody has seen before.

That’s what drives me towards venture capital.