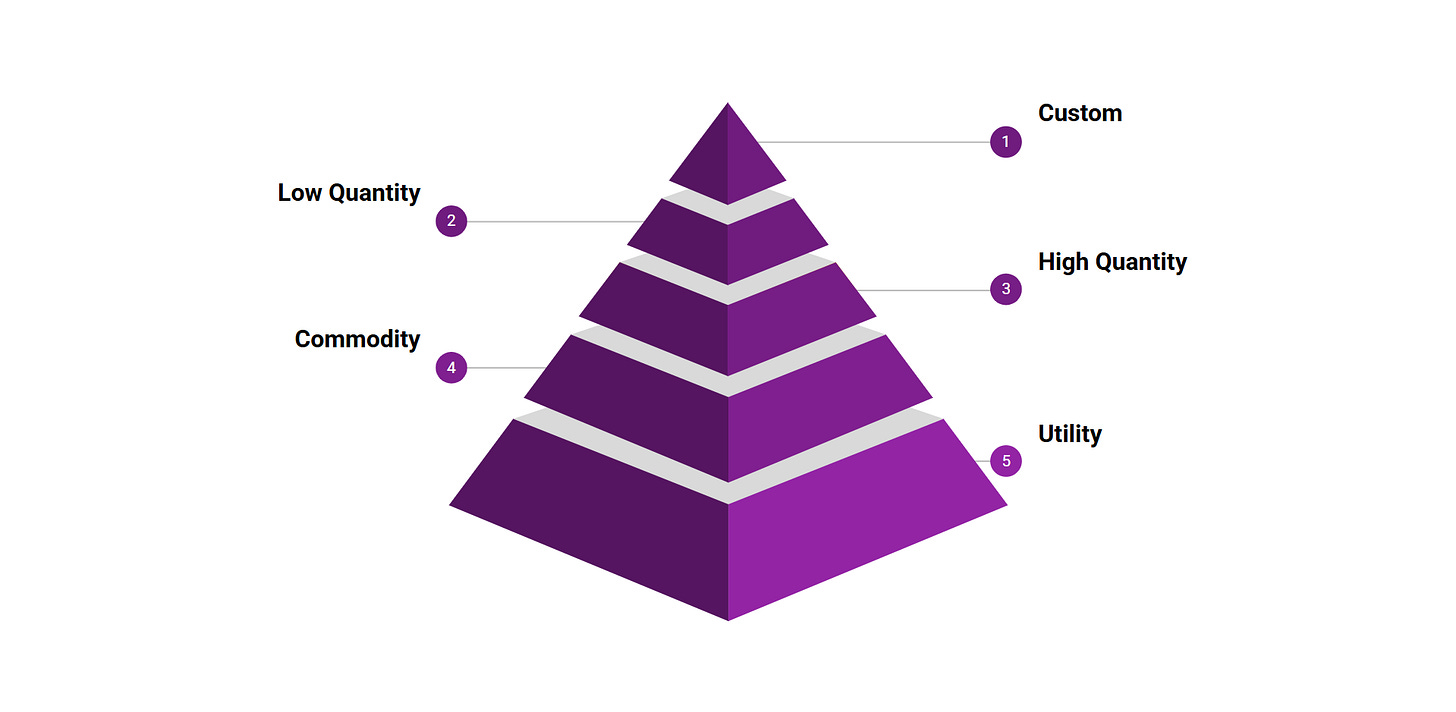

The Production Pyramid

What do blockchains and bolts have in common?

This weekend I’m attending the wedding of a friend from high school who I reconnected with when I moved back to Chicago. It reminded me of the first wedding of a friend I attended, several years ago in Memphis.

The afternoon before the wedding in Memphis, everybody was already in town. Somebody decided that all the groom’s friends needed to make a pilgrimage to the gigantic Bass Pro Shop in Memphis. As we drove across town, I recall being confused as to why we were visiting a camping supply store (that groom wasn’t an outdoorsman, so I didn’t see great potential for wedding schtick props).

When we arrived, I learned that not only were we visiting an American architectural icon, but we genuinely needed to go there — somebody had managed to make the trip in from out of state without a black belt, and it had them in stock at a reasonable price.

I’ve been reflecting on the belt and the pyramid in contrast with each other. The pyramid is a one-of-a-kind structure (regardless of whether or not it actually has architectural merit), while the belt is a high quantity consumer good.

The thing that’s fascinated me this week is just how much the size of a production run dictates the shape of a company.

The Pyramid

In my mind, there are five different types of firm in terms of firms categorized by product.

At the top, with the smallest quantity, are firms that make custom products. Everybody is in this space until they figure out how to scale production. Every product here is bespoke. This is how firms used to operate before the industrial revolution. Firms that operate in this space today for significant periods of time are often R&D-focused, and build things like experimental fusion reactors or custom structures.

Underneath that, producing slightly more product, are firms who sell products with low order quantities. These include companies that build things like container ships, or jet aircraft. The design has been standardized here, but production runs might just be a few pieces of work.

Moving beyond that are things produced in high quantity. The differentiator between low quantity and high quantity is probably the fuzziest thing here. On some level, it’s got to be arbitrary. Having said that, the distinction can be clearly illustrated. Just as container ships are low quantity, SUVs are not. And in much the same way that power plants are low quantity, smartphones are not. The gap between what market leaders in these fields produce each year is at least three orders of magnitude, and that’s enough to show a difference.

The next level down is those firms that sell commodities. Examples of commodities are nuts and bolts. What differentiates high quantity goods from commodities is that in theory, the vendor shouldn’t matter here because the products are exactly alike. While a hatchback made by Toyota might differ in some respects from a hatchback made by General Motors in ways that make them imperfect substitutes for each other, a 5/32” hex driver made by Tekton and a 5/32” hex driver made by StewMac should be totally interchangeable. So should bolts, and rice, and various other products.

The bottom level of the pyramid, utilities, consists of things that are available in abundance. Moreover, they are understood as having such big total addressable markets, and being so critical to human flourishing, that the government regulates how much providers can charge for them. Examples of utilities are things like consumer debt and utilities.

Great Companies Can Appear Anywhere

Critically, it’s possible to build a great business producing products at any point on the pyramid. Here, “great” doesn’t necessarily mean a unicorn outcome, though it does mean a business that eventually gets to positive free cash flow.

I am also confident that it is possible to build a billion dollar business in ten years selling any possible quantity of products. Examples of startups that fit in each category (from the top of the pyramid to the bottom) include Machina Labs, Joby Aviation, Bonobos, Apple, and Vital Lyfe.

These are all firms that have raised real VC dollars, though they are at a cross section of points in the startup journey. Three are exited (one through a SPAC, one through an IPO, one through an acquisition), one is growth-stage, and one is still very much early-stage. This illustrates an important caution about the pyramid: annual production quantity is going to affect everything about the firm. It’s upstream of who the right founders are in a space, as well as the right investors.

Investor-Market Fit

This issue of investor-market fit appears in two ways.

The first way is by looking at all VC funds as stage-focused. Many funds, particularly early-stage funds, market themselves to investors as investing mostly in one or two types of transactions. The firms become specialists in pre-seed deals, or seed deals, or Series A deals — and what they don’t invest in their target stage, they probably invest one round before or after, or reserve for follow-on investing. In this sense, most pre-seed investors underwriting Minimum Viable Product development will be at the top of the pyramid, and as a startup builds deeper commercial relationships, they’ll progress to funds that invest in products farther down the pyramid.

There is a difficulty with this understanding, and that is the multi-stage firm. Institutions in the VC world, like Sequoia, Bessemer, a16z, and certain Corporate Venture Capitalists, are almost as happy to invest in a seed round as a Series D, so they appear to break the model. It should be noted that these types of firms frequently have multiple funds, which may be sector- or stage-constrained.

However, there’s a solution. Some people analyze these multi-stage firms less as venture capitalists and more as asset managers. There was a kerfuffle last year when a16z said it might be getting into private equity, but it was really just an offering for its internal multi-family office. General Catalyst has invested significantly in this space, and now features a wealth management offering prominently on its website. Subscribing to this approach resolves the difficulty because if we say that at the firm level they’re really playing the asset management game, which is a distinct game from the VC game (though there are similarities). There might be overlap in the right investors between VCs and asset managers, but their incentives will be different, and that’s also going to impact investor-market fit.

The second way is only present in the early-stage market, and really gets at what companies plan to do one day.

Nuclear power startups illustrate this well. Lots of VCs are interested in the space, which is a change from historical norms (and is affecting reactor design). But the really interesting thing is that after around the ideation stage, there are almost no investors who invest both in nuclear as a sector, and say, men’s clothing as a sector within VC (which is the category I’d put Bonobos into). My impression is that within early-stage investing, firms looking to eventually produce different quantities of a product should speak to different sets of investors, who have minimal overlap.

Production quantity targets should also guide the long-term capital structure the company is building to. The effects of this in a successful startup are observable by studying Form 10-Ks; companies that manufacture more things often have a large line item on their balance sheet labeled “Inventory”.

How does software fit into this?

This framework was really developed for hardware and manufacturing startups, and simply not relevant to software.

I’m still unconvinced this is strictly relevant to most software firms, because the cost of a sale does not usually include custom development, engineering, or manufacturing efforts (notwithstanding forward deployed engineers).

However, I do think this framework is applicable to some fields within software.

I see crypto as appearing on the pyramid as a utility, at least to the extent that it functions as a currency alternative. The present financial system in the US uses fiat money, which is tradeable because the government says it is. That makes it regulated by the government, which makes it a utility.

More generally, blockchain technologies qualify as commodities when they use proof of work to generate new blocks on a blockchain. Because compute effort is (for identical processors) interchangeable, it is a commodity.

Technologies built on top of LLMs may belong on the pyramid as well, because LLMs often use token-based pricing. Tokens are portions of a text used by the LLM in breaking down user statements to understand them, as well as to generate answers. They’re not produced as much as they’re consumed, but they still drive firm economics in the same way most of the things discussed above do. Tokens are not equivalent to each other in the way tons of wheat are, but they are understood by models in a similar enough way that I consider LLMs commodities.