SPACs 101

Going Public By Getting Acquired

Let’s say you’ve built a moonshot successfully, and now want to exit. You could search for an merger or acquisition opportunity, or go public. Going public typically takes one of three forms:

Initial Public Offering (IPO), in which new shares are created and sold to the public

Direct Listing, in which existing shares are sold to the public

Special Purpose Acquisition Company (SPAC), in which the company merges with a shell corporation whose only asset is proceeds from its own IPO

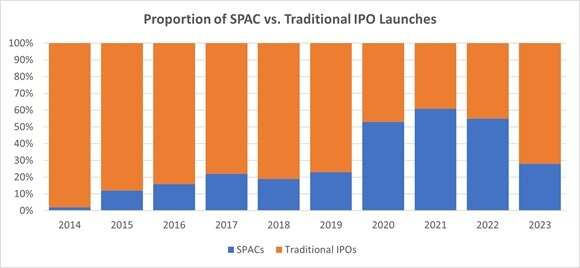

Historically, SPACs are a relatively uncommon way for companies to go public.

Their popularity has waxed and waned; their most recent peak was in 2021.

My former employer started trading publicly through a SPAC two years ago today, and conversations with senior leadership about that decision and process influenced my decision to pursue an MBA.

Today seems like a good time to talk about the transaction type, how it works, and what it means for existing stakeholders.

In one sentence, what is a SPAC?

In terms of mechanics, a SPAC is an Initial Public Offering (IPO) that merges with a company that has yet to be determined at the time of the IPO.

In terms of effects, a SPAC is somewhat similar to Entrepreneurship Through Acquisition in the sense that it involves one person raising money to identify and buy a company, but it’s typically an equity deal for minority ownership on the scale a publicly traded company.

How does a SPAC work?

Somebody who wants to lead a SPAC, called a sponsor, gets an executive team together.

That team goes through the process of an IPO. They write a prospectus telling investors about their plan to merge with a second company (a “target”), get approval from the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), do a roadshow, etc. Eventually, they start trading publicly on an exchange like the NYSE or NASDAQ, almost always starting at a price of $10/share.

In exchange for investing in the IPO of the SPAC, shareholders receive a unit consisting of a share in the company, as well as a whole or fractional warrant. This warrant, or the combined fractions of a warrant, represents a right to buy a share in the combined company at a set price on or before a specified future date, like a call option. The shares and fractional warrants start out tied together.

The proceeds of that IPO go into an interest-bearing account.

At this point, the SPAC’s executive can team start looking for a target to merge with. The SEC does not allow SPACs to go public with the intention of merging with a specific company. The SPAC has a predefined period to identify and close a deal with a target, otherwise they have to return the proceeds of the IPO with interest to current shareholders and stop operating. A term of two years, with shareholders able to grant extensions, is pretty common.

At some point during the search period, the fractional warrants will become tradeable separately from the shares in the SPAC.

Assuming things go well, the SPAC will have found a target. They’ll conduct due diligence, and make sure the business they’re buying is a sound one.

They’ll also negotiate the value of the investment with the target’s current management. The SPAC typically takes a minority stake in the target with the money raised during their IPO.

But that’s not all — the SPAC sponsor also gets equity in the combined company, as compensation for their effort in creating the SPAC and doing the deal.

The privately held company will agree to a merger. The SPAC will also call a vote of its shareholders to approve or reject the merger.

The SPAC will separately give its shareholders the opportunity to redeem their shares, or take their money out of the deal. Since the investors bought shares in a future, unknown company, the SEC says that they must have the opportunity to pull their money out of the deal after they learn what the deal will be. It is not uncommon for an investor to vote to approve the merger and also redeem its shares. The warrants are not redeemable and are either held or sold.

Investors pulling their money out of the deal is bad for pretty much everybody still in the deal, because if the target doesn’t get enough cash from the SPAC, the merged company could be left needing to raise more money soon, or even as a non-viable business.

To reduce the risk of this happening, investors use a Private Investment in Public Equity, or PIPE. In this type of transaction institutional or accredited investors purchase equity in a publicly traded company in a “private placement” (not on the public markets). This can be structured to stabilize how much money the target receives, and mitigate the impact of redemptions on the transaction. An example of what this might look like in terms of equity ownership is shown below.

After this, and appropriate regulatory approvals, the two companies will effectively combine and trade publicly on the exchange where the SPAC IPO’d.

What does it mean for entrepreneurs and earlier investors?

The SEC regulates IPOs very heavily. There are onerous reporting requirements and an S-1 registration statement that must be filled out as part of the process, essentially to protect retail investors from themselves. Private equity investments require certain qualifications to participate, so the government assumes the people making those investments are educated investors. When the general public has access to an equity offering, the government doesn’t feel like that’s always the case — so financial regulators attempt to protect us. They’re pretty good at their job; usually it works.

SPAC targets, however, don’t have this problem quite as severely. The SPAC has to go through the S-1 process, yes, but the target primarily has to file a Form S-4 with the SEC. That’s certainly not a walk in the park, but it’s not nearly as complex a process as all the pre-IPO paperwork. As a result, a SPAC merger can close more quickly than an IPO.

This makes the deals more attractive to all the involved parties because generally speaking, the longer it takes to do a deal, the lower the chances of that deal closing. This seems to hold true across all types of investment, from VC to IPOs and SPACs to PE.

Going public through a SPAC can involve a lot of dilution to existing owners in the company — often significantly more than a conventional IPO. Dilution purely in terms of control doesn’t really matter. After all, the target is seeking to go public, and by this point, the majority of targets will not be led by their founders. Dilution in terms of ownership is material though, in that it affects the economic outcome.

Here’s the pro forma (pitched by investors) outcome of Virgin Galactic’s SPAC roadshow deck from 2019, which assumes no redemptions.

According to the proposal, the SPAC’s owners will buy 35% of the company. The SPAC’s sponsor will own 14% of the company. This doesn’t even include dilution from the warrants! And the earlier investors will hold just 51% of the firm.

If the value of the enterprise has gone up enough, everybody will be happy, but this is a ton of dilution for all the earlier investors. Expressed as a percentage of the enterprise, IPOA’s sponsor, Chamath Palihapitiya, was compensated with more than 2x average fees on an IPO in the mid 2010s.

Virgin Galactic might be an extreme case, but the numbers aren’t great generally. Intuitive Machines went through a SPAC last February. Their pro forma ownership plot shows the SPAC sponsors holding 7% of the firm, which is closer to the normal underwriting fees for an IPO, but still above them.

When using a SPAC merger to go public, founders and early-stage investors can end up paying what amounts to a substantial fee for liquidity.

Furthermore, since a SPAC is a blind pool of capital, investors are entitled to pull out, or redeem, their cash from the pool after the investment terms are defined.

While it looks like SPACs have more price per share certainty in their mergers than traditional IPOs do in their underwriting due to the amount of money raised by the SPAC’s IPO, the ability of investors to take their money out of the deal after the terms are negotiated substantially affects this. PIPEs help ensure cash gets to the target company, but they can introduce undesired complications.

Based on recent performance, I can’t criticize investors for deciding to pull out their investments. SPACs tend to be smaller deals than IPOs, and recently the market seems to have a bias in favor of larger companies. The top ten biggest stocks by market capitalization (price per share * shares outstanding) represent more than 29% of all US equities. As a result, even without getting that technical, it makes sense that SPACs underperform IPOs.

This trend seems to have become even more extreme since the 2021 peak. It’s not a transient phenomenon, but the long-term trend could change.

This is material to founders, early employees, and venture investors because on consummation of a SPAC merger (or a traditional IPO), it’s common for existing equity owners to have a ‘lock-up period’ during which they are unable to sell their shares. This provision exists to keep the share price from dropping rapidly as trading volume increases. It has the effect of lengthening the period of time it takes these early shareholders to exit from their position in the company, and increasing their exposure to the market’s value of the company until they are able to sell their shares.

SPACs are an interesting alternative to traditional IPOs and Direct Listings that have unique benefits (potentially time to close, regulatory burden before trading publicly) and costs (dilution).

They’re typically a minority of go public events, and probably for good reason.