This week I’m excited to share another startup snapshot.

I’m writing about Quindar, a satellite operations software startup, for two reasons. First, it looks like Quindar did something interesting last year in terms of financing — it raised a seed extension round. Second, I know some of the founding team from an internship at a past company.

Problem

The spacecraft ground software stack is unwieldy to use and unpleasant. The code that engineers and operators on the ground use to operate a fleet of satellites is cumbersome.

There’s a lot of different things that flight operators have to do — monitor spacecraft status, send commands to space, receive telemetry from space, analyze data, book time on ground station antennas, alert on-call personnel, and more.

Each of these has multiple SaaS options, and not all options are compatible with all architectures. Each option also has a different user interface (UI), so there’s a real penalty to needing to train operators on every different tool a satellite operator uses.

Solution

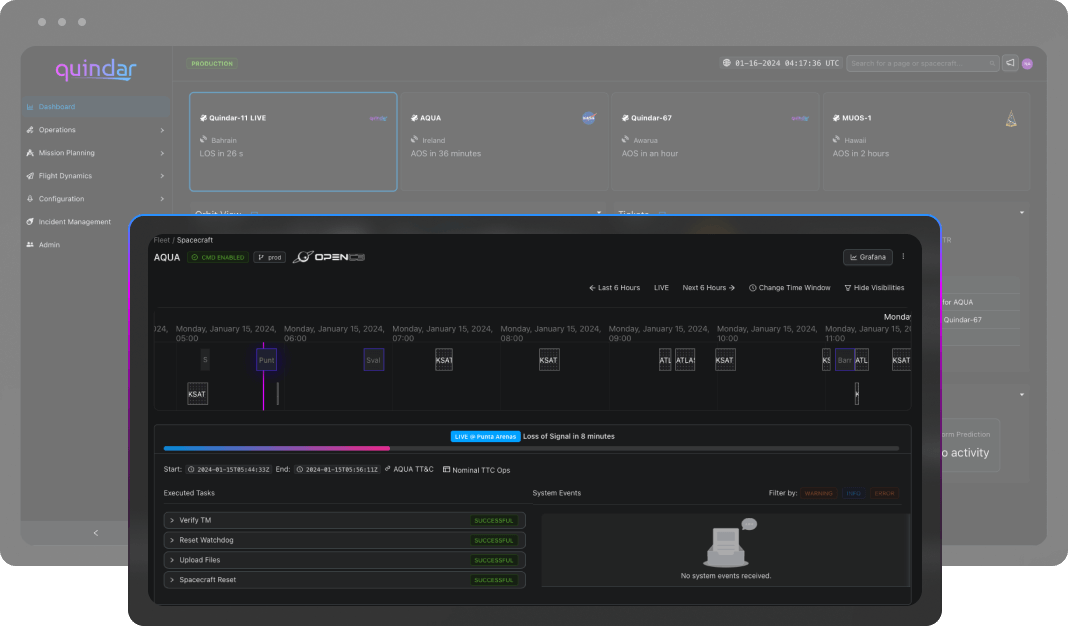

Quindar provides four different value propositions to customers, as shown in the image below.

It does this through a UI that has back-end integrations with many of the different tools used by spacecraft operators. This reduces the training burden for new team members, and should make it easier for them to do their jobs since they won’t be constantly switching between different tools.

It also makes it far simpler to communicate across teams when everybody involved is using the same interface for their workflows.

What Quindar does that I think takes it to the next level, and might be unique, is apply this same philosophy even before the spacecraft launches: it’s interested in flight operations using the same software as the vehicle manufacturer uses.

What’s in the name?

A Quindar was a beeping sound triggered by the engagement or disengagement of a push-to-talk space-to-ground radio in early American space missions.

Wikipedia’s article about the tone provides a sample:

Quindar is an elegant name for a startup focused on simplifying space-to-ground interfaces.

Founders

Interestingly, none of the founders identify themselves as such on their website’s Team page. Y Combinator lists six founders.

The common threads in their careers are time spent at OneWeb, which offered a service that competed with Starlink, and Orbital Effects, a SAR satellite company. All of them also have technical academic backgrounds. I have no concerns about founder-market fit.

Nate Hamet is the CEO, Matt Regan is the Head of Operations, and the other four founders are identified as Principal technologists of some kind — Sunny Bhagavathula is the Principal Product Engineer, Dave Lawrence is the Principal Mission Architect, Shaishav Parekh is the Principal SWE for Platform, and Zach Meza is the Principal Software Architect.

Their short bios on the website provide links to their LinkedIn accounts. This is an elegant way to provide interested website visitors with the more detailed background of the founders, if their profiles are built out.

I overlapped with much of this team at OneWeb when I interned there through the Matthew Isakowitz Fellowship Program. I specifically remember meeting Nate for the first time, and working next to Shaishav all summer long. My experiences with them were positive. I did not speak to them about this post.

Everything in this post either is based on publicly or commercially available information.

Market

Top-down

Future Market Insights thinks the satellite ground station market was worth $72 billion in 2024 and will be worth $274 billion by 2034. That’s a CAGR of 14.3%, though the US-specific CAGR is a couple points higher.

Markets and Markets saw the ground station market was worth $61.5 billion in 2023, and thinks it’ll be worth $115 billion by 2028, which suggests a CAGR of 13.4%.

Polaris Market Research thinks the ground station market will be worth $191.6 billion by 2032, and has a CAGR of 13.3%.

There’s clearly consensus that the market is going to be at least $100 billion by 2030, and that it’s growing at a faster rate than the US economy, which has an annual GDP CAGR of 2.5% between 2014 and 2024. The rate of growth might be slowing down, but it’s still quite large, and the market is already fairly big.

Using SaaS norms from the past decade, a successful software startup has to hit about $100-$200 million in annually recurring revenue to become a unicorn — which is a very small fraction of these market size projections. That’s important because I expect the SaaS market within the sector to be worth at most 50% of the market size. I don’t think it is all that much bigger because the optical or radio communications equipment required to operate in this sector is expensive and complex.

Bottom-up

Working from the bottom up, the TAM is going to be a function of satellites worldwide that are flying in ten years. But as a result of the protectionist nature of spaceflight policies, the SAM is much more useful, and is most easily defined as the number of American satellites not operated by SpaceX that are expected to be in space in a decade.

Statista says that as of November, which is the most recent date for which I can find data, the US had 8,530 satellites. Government-operated satellites are within scope because Quindar is interested in selling into the defense industry. SpaceX-operated satellites (Wikipedia says Starlink has 3,454 active ones) are not, so there are 5,076 US satellites Quindar could potentially provide services to.

The US GDP has grown 2.5% over the past decade; let’s say the number of satellites grows at three times that rate annually that over the next decade. Based on the top-down estimates, that’s pessimistic — so I’m comfortable with it. In 2035, I expect to see the US, aside from SpaceX, operating about 11,240 satellites.

Quindar’s value proposition is mostly in interface simplification and acting as a data pipe — spacecraft operators will still need to access to flight software tools, antenna time, command and control software, etc. Most satellites are small satellites, which typically cost well under $10 million to product. Let’s say the average across all satellites is $8 million.

With an expected active lifetime of around 7 years, and most satellites operating fleets of multiple spacecraft, I expect operators are willing to pay at most 1% of the spacecraft cost per year for ground software interface management. That’s $80,000/year/vehicle.

Multiplying that times the number of satellites, there’s a SAM of almost $900 million/year. This comes just from the flight operations side of things.

If a satellite has a projected lifetime of 7 years, there should also be a material market for the services Quindar provides from vehicle and component manufacturers.

George Box said that “All models are wrong” — to which many add “but some models are useful”. This quick model shows me that Quindar could hit the revenue benchmarks would lead to a unicorn valuation within ten years without needing to win a majority of its SAM, if enough things go their way.

Fundraising History

During the summer of 2022, Quindar participated in Y Combinator’s S22 batch. YC’s standard deal purchases 7% of the startup’s equity plus a variable amount based on an uncapped MFN SAFE.

In January 2023, Quindar announced that it raised a seed round, ultimately securing a $2.5 million investment. Key investors in this round included YC, Soma Capital, FCVC, and others. Notably, Pitchbook asserts that this round included $0.33 million of venture debt, and that the post-money valuation was $22.5 million. This is consistent with my understanding of post-YC fundraising norms.

In January 2024, Quindar announced a $6 million seed extension round. According to Pitchbook, Fuse led the round, and YC followed on again. Pitchbook says that the post-money valuation here was $40.5 million, and that by this point, investors owned 27.57% of the firm. This round seems to have a more explicit goal than the earlier seed round, which is to start building AI-driven insights into the services.

In July 2024, Booz Allen Ventures, a strategic investor, announced an investment in Quindar. Booz Allen Ventures is the VC arm of Booz Allen Hamilton, a leading government services contractor that has a special focus on defense and national security missions. Pitchbook identifies it in the context of the seed extension round, though it may have been done separately.

Selected Competition

The playing field here isn’t empty, but it also doesn’t seem to be many companies’ priority. Some notable alternatives include:

Xplore — Major Tom has some similar functionality, to the point of overlapping integrations

Major Tom was acquired from Kubos

This is a secondary product line for Xplore

D-Orbit — Aurora has comparable functionality, to the point of overlapping integrations

This is a secondary product line for D-Orbit

Turion Space — Starfire is a somewhat comparable product

This is a secondary product line for Turion Space

SatNOGS — an open-source ground station software tool

It is the least complete alternative, but it is critical to note that there is an open-source solution to some of the problems the startup is solving

I’d like to get into the practice of doing plots showing relative valuation/cumulative fundraising when there’s data available. However, I’m not sure any of these comparable startups are actually priced based primarily on this type of product, so I don’t think that’d be valuable here.

Technology

The key technology here is API integrations, and stacking a User Interface that’s pleasant to look at on top.

This is spaceflight software, but it looks much more like business-to-business software as a service than deep tech.

Progress

Quindar’s progress so far seems to consist of three main things.

First, it won a $1.2 million contract from AFWERX, the innovation arm of the Department of the Air Force. DoD funding, if it can be secured, tends to be consistent and perhaps not as price-sensitive as other startups are. An AFWERX contract is a great place to start building this relationship.

Second, Quindar has secured some really key integrations with ground station as a service (GSaaS) providers like ATLAS Space, KSAT, and Leaf Space Network. It’s gotten other essential service partnerships set up as well with companies like GitLab, Bitbucket, and Grafana — but the GSaaS providers are the star of the show here because they’re the pipes through which data flows to space.

Finally, and perhaps most critically, it is worth noting in addition that their pricing page has live links to a calendly account — so it is sufficiently far along in product development to be doing commercial sales actively, and generating revenue.

Assumptions

In order to seriously consider Quindar as a potential investment candidate, I’d have to accept these key assumptions:

The trend in constellation operations is towards a unified software interface

The company can line up integrations with SaaS providers covering a significant portion of the markets that it is interested in rolling up the interfaces to

There is value to firms that operate satellites and are not vertically integrated in using the same software interfaces as their spacecraft vendors

Key Open Questions

If I had more time, these are the most significant questions I’d dig into.

Who is their beachhead market, and why?

Which SaaS providers is Quindar negotiating with?

Who has Quindar decided to not work with?

Why is it worth more than $40 million?

Final Thoughts

This is an interesting startup.

One of my gripes about the space industry is that it’s not very good at selling to anybody but the government, and that caps the sector’s ability to grow. I see startups like Quindar as part of a solution to that; by requiring manufacturing personnel and spacecraft controllers to learn only one UI, operational barriers to entry are broken down. That should make it easier for new types of institutions to get a foothold in space.

Quindar exemplifying the “Saasification” of satellites is also exciting to me because it shows that space is no longer just the domain of deep tech. I’m driven by an interest in emerging technology, but the space sector will only actualize its potential to change the world and take humanity to new ones after enough people get comfortable with it.

From my experience with the founders, I have high confidence in their technical abilities.

The seed extension is a potential red flag from the financing side, but also shows that the founders are rational about their expectations for valuations, which I see as a good thing — especially for a founding team that’s entirely technical.

I look forward to following Quindar and watching its growth going forward!