Media Review: Chip War

The Story of Moore's Law

As an investor at a deep tech fund which gets excited about hardware startups, I decided earlier this fall to start studying how more types of hardware get made. The best place to start seemed to be at the lowest level of complexity in a computing device — the integrated circuit, or chip.

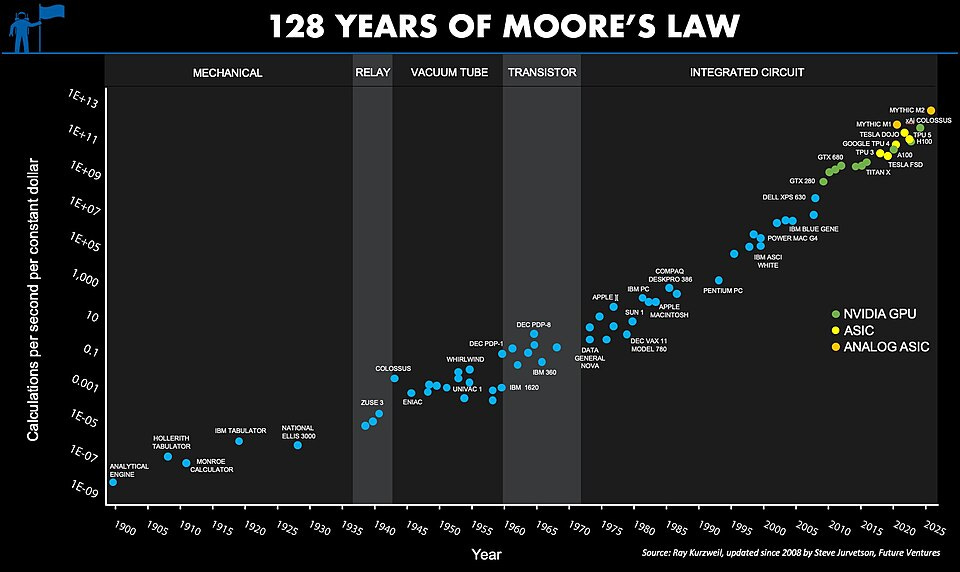

I remembered hearing back when I was a computer science student that the number of transistors on microchips doubled about every two years; this is known as Moore’s Law.

I sought out a book that went over the history of this observation in a non-technical way, and nearly every source I found recommended Chip War.

Content

The author kicks off the book by establishing the story of integrated circuits within a period of increased tension between the US and China. He sets the scene of a US Navy destroyer transiting the narrow body of water that separates China, the world’s largest semiconductor market, from Taiwan, home to the largest contract chip manufacturer in the world (and counterparty in a long-lasting territorial dispute with China) during a period of increased tension between the US and China. This leads into an introduction that provides a very brief survey of the chip-making industry and its history.

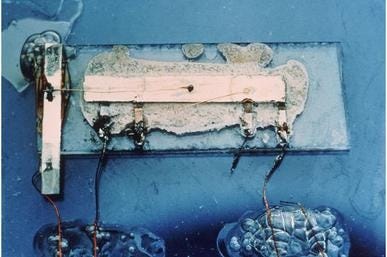

The book starts in earnest at the beginning, by discussing World War II-era vacuum tube computers. The second chapter covers the development of the transistor theorized by Shockley.

The following chapter covers the development of the integrated circuit, as well as the “traitorous eight” who founded Fairchild Semiconductor — and really started the entrepreneurship phenomenon that defines modern Silicon Valley.

.The following few chapters cover more of the Cold War from the perspective of the defense sector, from long-range nuclear weapons, to smart bombs, to Soviet espionage. As the text develops, the market becomes more commercially-focused than government-dominated, and the narrative surrounding it also shifts.

Chapter 6 is noteworthy because it introduces Moore’s Law. Gordon Moore, then-head of R&D at Fairchild, predicted in ‘65 that every year, at least for the coming decade, his company would double the number of components that fit on a single silicon chip.

The general theme of the book is how this prediction has held true for far longer than Moore initially anticipated, and how the industry has changed radically, many times, without breaking the pattern.

The book crosses oceans, from the origins of Silicon Valley, to Soviet espionage operations, the Japanese capture of DRAM chips, the creation of Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company, the development of Extreme Ultraviolet Lithography machines, the appearance of South Korean manufacturers, the trials faced by US companies like Texas Instruments and Intel, and especially China’s sustained effort to develop best-in-class chips for all its markets.

If Moore’s Law describes the technical journey the book takes, competition between the US and China really characterizes the political narrative. In fact, if one were to know nothing about post-1945 history before reading this book, a reader could reasonably come to see the Cold War really as a warm-up for the emerging US-China conflict in the chip space.

The book frames chip supply chains as the most critical supply chains out there for modern life, and goes as far as to suggest that it might be an example of globalism gone too far.

Modern high-end chips require equipment made in the Netherlands (which has suppliers in the US), software made in the US (but which may have been made by a German-owned company), and fabrication facilities in either South Korea or Taiwan.

To the extent that Chinese firms’ access to chips creates national security issues for the US, it seems that American political leadership has struggled to effectively regulate those companies’ ability to buy chips.

The book suggests that this sort of closely developed cooperation creating a new domain for conflict isn’t actually unique, which I think is really interesting. The other parallel industry is banking; the US has leveraged other nations’ dependence on its financial infrastructure to really make sanctions sting against other hostile countries and their leaders.

The book doesn’t conclude with a prescriptive call to action as much as a reminder of how complex this sector is, and the importance of commercial markets in supporting the development of new technologies.

Organization

This book is divided into eight parts, each of which is subdivided into a total of 54 chapters. There is also an introduction, a conclusion, and a cast of characters.

Part I: Cold War Chips, looks at the early history of digital computing, contextualized squarely in the defense industry.

Part II: The Circuitry of the American World focuses on stories of advanced US chips and how they impacted other countries during the Cold War — like the USSR, Hong Kong, Singapore, and Vietnam

Part III: Leadership Lost? studies how the US lost its market-dominating position in much of the chip industry over the course of the 1980s, much of it to Japan

Part IV: America Resurgent explains how chips enabled the US to win the Cold War.

Part V: Integrated Circuits, Integrated World? shares how the industry was impacted by the end of the Cold War and the globalization of the 1990s.

Part VI: Offshoring Innovation? retells the search for capital efficiency, and explains how the supply chain in this industry has taken its modern shape.

Part VII: China’s Challenge spotlights the history of the industry in the People’s Republic of China, centering this narrative.

Part VIII: The Chip Choke looks at the recent political history of the industry, from the end of the second Obama administration through the early Biden administration.

The scope of this book is broader than anything I’ve reviewed so far. It’s not the story of a firm, like Becoming Trader Joe. It isn’t the history of a particular competition, like The Space Barons. Nor is it even the history of a sector within a country, like Money of the Mind.

Chip War is the history of an international sector of the economy. The book’s scope is frankly bewildering, stretching across characters, companies, decades, continents, and types of corporate structures.

Despite the author’s best efforts, I found it difficult to follow the action across chapters.

There were points when I felt I had to stop reading because I was so confused as to what was going on, and moments where I wondered whether this would have been better structured as 54 separate essays on elements of the industry.

In the end, I pushed through — because, as is often true in the semiconductor industry, there simply wasn’t a better and clear path to solving the problem.

How well does the book achieve its goals?

When I sought out this book and started reading it earlier in the fall, I was hoping for a break from dual-use topics. I didn’t find that here, but that’s ok.

What I found in the context of defense references was a synthesis of Silicon Valley (the region I now call home), commercial telecommunications, personal computing, and many of the most valuable companies in the world today.

It is an honest, if US-centric, survey history of the semiconductor industry. And that’s exactly what I believe this book is trying to be.

I write Molding Moonshots in a personal capacity.

If you are building in deep tech and thinking about raising pre-seed, seed, or Series A funding, I’d be more than happy to have a chat on professional terms!

Send me an email and we can find a time.

Final Thoughts

While it had more of a dual-use focus during the Cold War, in its more recent history, Chip War focused far more on the geopolitical implications underlying the semiconductor industry than I’d anticipated.

This makes some sense after thinking about the time that’s passed — most technical innovations in post-Cold War technology are probably still classified.

But it made so much more sense after reading the author’s biography. Chris Miller teaches international history at The Fletcher School, one of America’s better-regarded graduate programs for the study of international relations. He certainly comes across as pragmatic on foreign policy.

I think the political dimension makes it more accessible than it would otherwise be. Even as somebody who enjoys reading technical papers, I’m not sure how well I’d react to a book this long if it was just a technical history of the sector. The historical-political elements of the narrative do much to make it more exciting, more readable, and more popular.

I found his style very clear, and honestly delightful, within each chapter. He opens up most with a narrative vignette. From there he explains in a more matter-of-fact way what the story shows evidence of more broadly, and frequently connects that to other themes.

I’m not necessarily obsessed with Chip War as a singular book. At this point, the topic of semiconductors is just too broad for a single tome of this thickness.

But I think it works much better when it’s approached as fifty-six essays about the history of this vital element of the global economy.

Love this!