Last month, I read Becoming Trader Joe as a book that’s illustrative of the idea that a VC investor should study great businesses in general.

This month, I doubled down on the consumer theme by reading Ask Iwata: Words of Wisdom from Satoru Iwata Nintendo’s Legendary CEO.

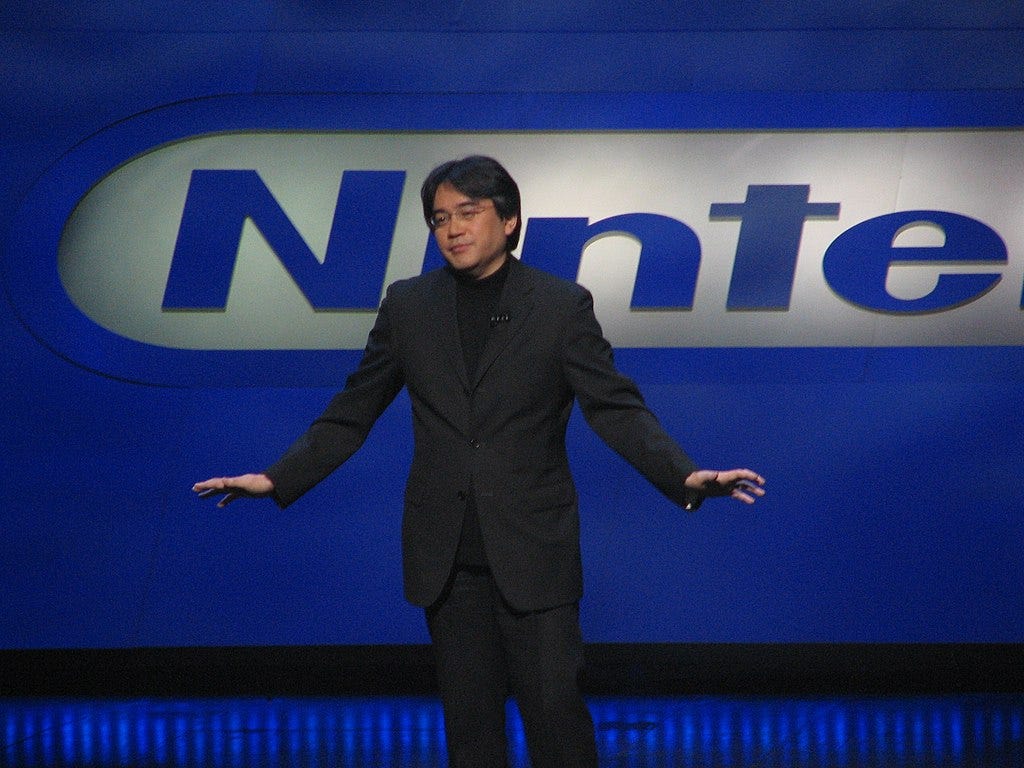

There are two critical differences I want to highlight between Satoru Iwata and Joe Coloumbe.

First, Iwata was a CEO of a sizable Japanese corporation, which is likely going to have a radically different structure and culture than a startup grocery store in California. Just as it’s important to cross sector boundaries in reading about great businesses, it’s also important to jump across geographies, cultures, and corporate structures.

Second, Joe founded his firm. Satoru did not. That’s going to affect how their leadership is perceived by other stakeholders, even if it doesn’t actually impact their leadership.

Organization

Normally I place the content first in a review, but the organization here both feels remarkable and contributes to the character of the text.

Ask Iwata is an unusual book because only the preface seems to have been written with the intent that it should be a book. Rather, most of it was developed by Iwata as content for the website of Hobo Nikkan Itoi Shinbun, or from the Iwata Asks portion of the Nintendo website. The remainder are mostly obituaries or reflections from people close to him.

The book is quite short, only 154 pages. There are seven chapters, each of which covers a different facet of Iwata’s life.

Chapter 1, “Iwata, future President”, provides anecdotes of his early life — from secondary school through running HAL Laboratory.

Chapter 2, “The leadership of Iwata”, shares his perspectives on leadership and management.

Chapter 3, “Iwata, the individual”, discusses his personal philosophy.

Chapter 4, “The people Iwata believes in” covers his impressions of his collaborators — principally Shigero Miyamoto (a long-time collaborator), Shigesato Itoi (who designed EarthBound), and Hiroshi Yamauchi (the immediate past president of Nintendo).

Chapter 5, “The games Iwata strives to make”, shares his opinions about the projects which defined his career. It also covers his views on the philosophy of games.

Chapter 6, “Remembering Iwata”, contains obituaries and reflections from colleagues that were written after his passing. It is the longest chapter.

Chapter 7, “Iwata, the person”, is a conclusion that gets at Iwata’s intellectual curiosity. It is the shortest chapter.

All chapters contain a number of quite short, almost independent pieces that are fragments from the source texts. Sometimes adjacent pieces are directly related, but not always. And the way the book is printed puts less text on each page than I’m used to. Each piece is named in the table of contents, which I really appreciate.

Each chapter, except the penultimate one, ends with “Iwata’s Words of Wisdom”, a series of shorter quotes from him in bullet point format on the topic of the chapter.

Content

This is the first book I’ve reviewed here that I read in translation; the source text was all written in Japanese.

This book is not the history of Iwata, or of his time as CEO of Nintendo.

Stepping back even more, this is not a conventional book, which typically contains a plot with rising action, a climax, and a resolution.

Instead, there’s a derivative of a plot, which is the life of Iwata. Readers never encounter it directly though; we only hear what the characters wrote and said about it. This book only shows, it never really tells.

The text discusses the various products Iwata was involved with, from games like EarthBound, characters like Kirby, and hardware products like NintendoDS and the Wii. But it’s not about these things as much as the person who facilitated their development. The book keeps on coming back to this idea that Iwata was an excellent software developer, and an even better leader of people.

This comes through in his personal philosophy, in that it spends some time discussing how he thought about creating code, but it spends much more time sharing his views on game design and working with people.

He and the editors seem to have been very careful with his words. Indeed, the only thing in the book that Iwata attempts to clarify is his famous quote:

Programmers should never say no

This has got to be one of the statements he was best known for at Nintendo, because it’s something that he brings up initially to clarify it, and that somebody else mentions in Chapter 6.

The point Iwata makes about this is that when trying to create paradigm-breaking products, saying “no” is going to inhibit game designer creativity, and restrict possible future work. However, that’s only objectively bad in an unconstrained game development environment, so what he really means to say is that nothing is impossible. The obituary writer also reframes it, though his interpretation seems to be more specific. This view understood it as saying it was the developers’ job to create a structure so the game designer can share their vision openly.

Speaking of game design, Iwata makes some intriguing observations about the field. I’m sure a good deal of them are lost on me because I am not in the business of making games, but a few really resonated:

The philosophy for Wario was all about doing things that Nintendo hadn’t historically been able to accomplish

Sometimes, the fastest way to complete a project really is to throw everything out and start over

Games are fundamentally a platform for interactive play

This last point really resonated with me. I recall feeling frustrated as a middle schooler playing on the Wii, and struggling with some external publishers to beat levels in video games.

Video games are particularly fascinating to me in an aesthetic sense because they’re the only sort of artistic medium where the artists come across as having the desire, let alone the capacity, to tell their audiences “no, you are not good enough to see the whole piece”. At the same time, I know from experience that the sense of happiness that players feel when they do see the whole thing is real — and this comes across throughout the text as having been a driving force for Iwata.

The majority of the text, however, is spent looking at Iwata as a colleague, and as a leader of people. He talks about a number of business practices, from dealing with debt when he first became a CEO, to studying bottlenecks and interviewing employees, to inspiring people and management in a more general sense. There are two ideas here that sound especially compelling to me, and that I understand as particularly applicable to the entrepreneurial world.

First is his point that nothing is more dangerous than staying the course. He thinks that deciding to not attempt to innovate is intrinsically risky.

Second is his idea that one should play games they think they can win. This speaks in a direct sense to how gamers spend their time, and also to people at work.

How well does the book achieve its goals?

While the book dances around a plot, it is quite explicit about its objective — which is the opposite of most books I read for fun.

In the preface, the objective of the text is to bring together as many of Satoru Iwata’s insights as possible into one volume. This is a memorial, written to share his philosophy with his devotees and as many other people as the editors can interest.

I never met Iwata, so I can’t speak directly to how well this goal was achieved.

However, I am left with the impression that Satoru Iwata’s largest goal in life was to make people happy, and he directed his immense creativity to that end by developing games and software. He had insatiable curiosity, which he applied to everything from learning new programming techniques, to reading books about business, to studying behavioral economics.

He was respected and well-liked by his colleagues, supervisors, and employees — as well as a devoted family man.

Not that this comes from the book, but from my friends who have played his games, I know that he was successful in bringing people happiness through them.

Final Thoughts

The structure and content here is elegant, precisely the sort of thing I’d expect to see about a game designer. Readers encounter his personal history, learn about his philosophy regarding leadership and in general, meet his colleagues, learn about what he accomplished with them, hear directly from his colleagues, and wrap up with some brief thoughts from the subject of the text.

Satoru Iwata must have been a very special person, and deeply committed to spreading happiness through games.

I was stunned by how much of his advice was from the world of gaming, but not just of it. As I read the book, I noted just how many of his ideas have relevance in entrepreneurship, engineering, investing, and life more generally. This book may not belong on my desk, but it’s earned a spot on my bookshelf.