Investing in AI in 2025

Bullish on the tech, bearish on the prices

One of the biggest trends in 2024 was the growing role that AI, particularly Generative AI, plays in our lives.

I’ve been both startled and incredibly impressed by the advances in AI technology over the past year.

From generating images (though never text) for this Substack, to taking notes on conversations for my classmates, to performing surface-level research on new topics of interest, Generative AI had a really breakout year in terms of technology available to end consumers. The increased adoption isn’t just limited to younger people like me and my friends — I’m seeing mid-career white collar professionals post about it on social media regularly.

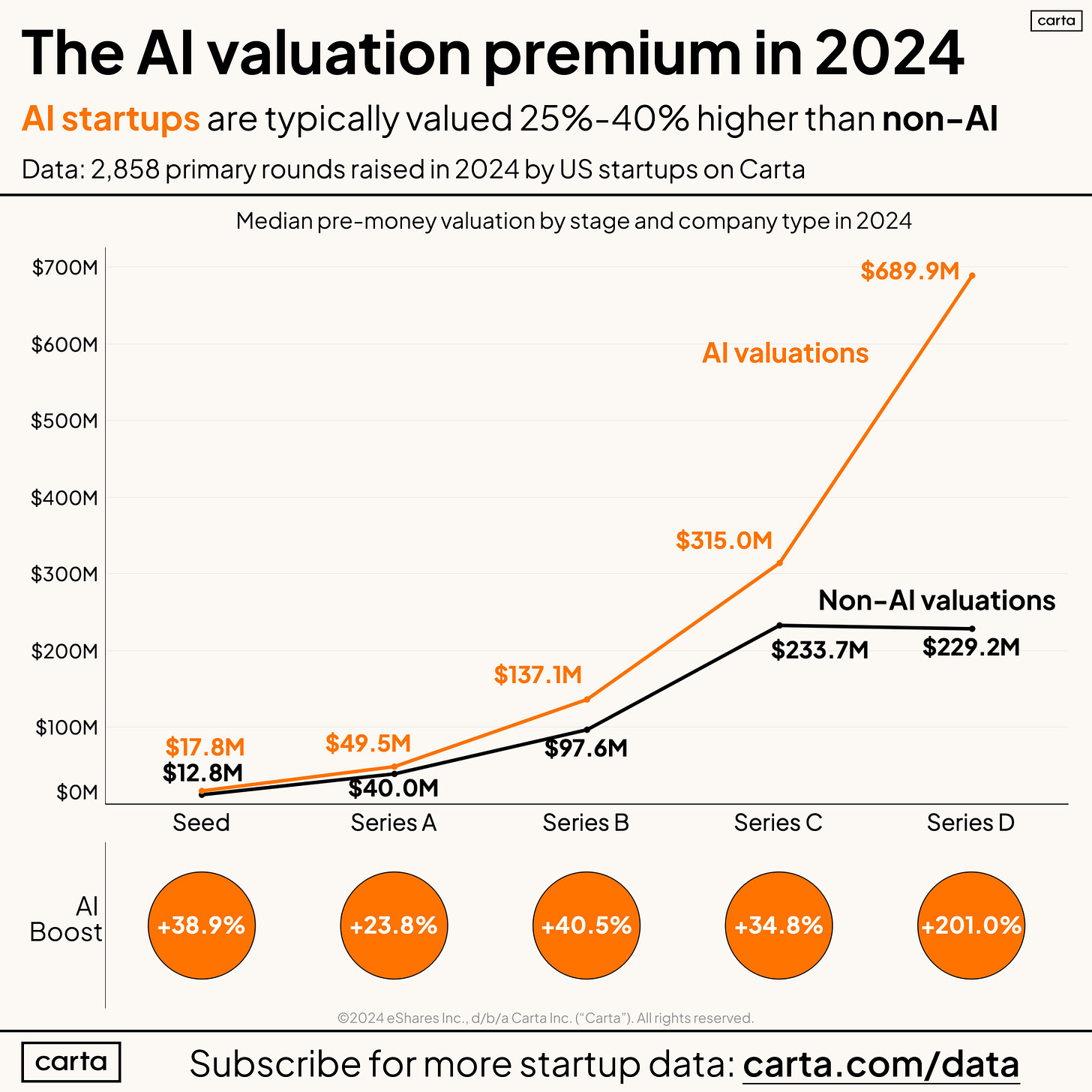

At the enterprise level, excitement about AI has been building too. I think this was perhaps most true in the startup ecosystem — surprisingly and particularly in fields not focused on AI. Peter Walker at Carta has a great infographic demonstrating this.

While the data is only for 2024, my intuition as an early-stage investor is that almost all of these categories showed growth in AI penetration year-over-year. Artificial Intelligence, as a category of technologies, has become much more widely accepted and accessible over the past several years.

Moreover, outside edtech, biotech, and energy, AI deals seem to be larger than non-AI deals. It makes sense to me why biotech and energy deals tend to be smaller; the thing that ultimately drives value in those fields is new compounds (in biotech) and energy (in energy), and AI today is at best ancillary to that. But I was particularly surprised to see education AI deals be, generally, smaller than education deals without AI, both because I see GenAI tools used so much in my university and because I view it as a real force multiplier of sorts for teachers and other educators.

My final takeaway here is that it’s still necessary, but not really sufficient, to market a startup as about AI anymore. Founders need to be “AI and X” in order to differentiate themselves and win an outsize slice of the funding available.

VC being a power law industry, I’m not sure how much of this is normative vs concentrated in the hottest deals. It’s also not clear from the graphic how true this is at the earliest stages (angel and pre-seed rounds). It’s seems to be true at the early stages (seed and Series A rounds) but becomes far more pronounced as startups mature, as Walker shows with another great graphic.

As he put it in the accompanying tweet — “if there’s a bubble, this is it”.

What would a bubble mean?

Walker’s point is worrying for me, because startups are illiquid investments. Startups are often seen as taking about ten years to get to a point where a later-stage exit or IPO is a realistic outcome — though this is subject to all sorts of other things outside the startup’s control, like market conditions, the IPO window, etc. Recently, these other things have stretched out that ten year notional holding period; it’s taking longer for startups to exit.

If there’s a bubble, that means entry prices will be higher than they “should” be.

So in order for me to think any early-stage investment, let alone an AI investment, is a good idea, I have to believe that a VC-scale outcome is possible within 8-12+ years, even if they’re building in a sector with a bubble that pops before then.

The alternative to a bubble is that this adoption of AI is a paradigm shift in technology. While this may be true for users, I’m not inclined to believe we’re at this point from a financial perspective, because I don’t see a new revenue model for AI right now. For me to be well and truly convinced that we’re seeing a truly transformational moment in technology from an investor’s perspective, I think we’ll need to see changes in how it’s paid for as well.

How would a bubble impact VC outcomes?

What constitutes a VC-scale outcome? It varies by stage, but is typically most conveniently expressed as a multiple on invested capital (MOIC). Series A investors, for example, are looking for a 10x MOIC — when the startup sells, their share of the ownership (which will likely have decreased since the startup has raised more money since their investment) should be worth 10x their investment. Earlier stage investors have to seek out even higher multiples, as the attrition rate is higher for younger firms.

But all these concepts without numbers can get confusing, so let’s work an example.

Let’s say I invest in 3 startups’ Series A, and buy 15% of each company for a price between $5 million and $10 million. After the deals close, I own 15% of each startup.

Now, let’s say each investment goes well and becomes a unicorn. As this happens, I get diluted so I own half the part of the company that I bought (7.5%) when it’s time to sell — which is fine, a smaller piece of a much bigger pie is the healthy dream for both investors and founders.

When the startups sell for $1 billion, I’m entitled to 7.5% of the proceeds. However, Startup A looks to my investors like a much, much better investment than Startup C. By locking up their money in Startup A, they got back 15x what they gave me, but by investing in Startup C, they only got 7.5x.

The key takeaway from this is that entry price drives MOIC.

Exit price and dilution can also drive MOIC, but those are a lot harder for an early-stage investor to anticipate or control, as board composition often changes with each major fundraise, and incentives between representatives of each round are not always perfectly aligned.

I advocate for everybody to focus on what they can control, and for early-stage investors like me, that’s the entry price.

There is a school of thought that says founders should take as much cash as they can, so Startup C is really the best outcome for founders. I tend to disagree because I believe who is allowed on the cap table and on the board matter. Furthermore, I’m convinced that founders having sufficient skin in the game and showing the right sort of growth between fundraising rounds are both critical to attracting the best investors at each stage. My impression is also that overcapitalized startups are more prone to failure.

AI’s had such an impact on the tech and VC industries over the past several years that if there’s an AI bubble, I expect average VC outcomes as expressed in MOIC will be depressed. I would anticipate a lot more Startup C-type outcomes at best (and more acquihires and shutdowns).

On the other hand, if there’s no bubble, Startup A-like outcomes will continue to happen, probably at an increasing rate as AI startups mature.

Is the bubble real?

I tend to think we’re in an AI bubble, because I view such a big gap between AI and non-AI firm valuations as unsustainable.

First, I’m unconvinced that being an AI startup justifies the premium mid-to-late-stage AI startups command today.

Even if it is justifiable today, it’s going to be totally unjustifiable tomorrow when every founder sees that they can get a higher valuation by pitching their startup to investors as an AI startup.

Beyond the bubble, I’m anxious about where the value-add from new AI technologies is actually going to end up. I’m concerned the model vendors and hardware suppliers will take this opportunity to grow bigger, leaving little to no margin for startups. Project Stargate, which has been described as a moonshot, doesn’t make me particularly optimistic.

But that does not mean I’m all doom and gloom, or that I won’t touch AI with a ten foot pole.

As a category of startups, I believe AI will continue to mature this year, and I hope to help great founders be a part of that transition.

I remain excited and ready to support the most brilliant founders I can find, in whatever field they’re leaders in — and this includes AI. I just have an obligation to be price-sensitive.

The challenge that I anticipate will define this year is finding win-win opportunities, where the potential to meet stage-specific MOIC targets exists. I see that as a function of both the size of the market founders are building for, as well as the entry prices they are excited about.